41 percent of Kanye’s videos can make you seize

Posted: 09/08/2015 Filed under: Music Videos, Results of safety testing | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures Leave a comment

Kanye West accepts the Video Vanguard Award during the 2015 MTV Video Music Awards on August 30 in Los Angeles. (Photo by Kevin Winter/MTV1415/Getty Images For MTV)

Because Kanye West received the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at last weekend’s 2015 MTV Video Music Awards, and because there were seizure risks found with some of his videos, I wanted to know how many of his music videos pose that risk. I wrote previously about a couple of his videos— All of the Lights (2011), and Lost in the World (2012)—that contain seizure-inducing images. Another one I wrote about for its seizure-inducing content, N**as in Paris (2012), was made with Jay-Z.

So in the week since Kanye was recognized for his achievement in music videos, I’ve tested as many of his music videos as I could—46—to determine how many contain flashing/moving image sequences capable of triggering seizures in sensitive individuals. My sample included only videos where Kanye is the primary performer, where he would have had artistic control over the visuals. I didn’t include those made jointly with Jay-Z or if Kanye was a featured guest on a video made by other artists.

41 percent of Kanye’s videos —that’s 19 of 46—could give you a seizure if you are vulnerable to visually induced seizures. OK, but has he stopped releasing videos that can bring on seizures? Did Kanye change his production style after UK-based Epilepsy Action called out the problem videos a few years back? Nope. The two videos I tested from 2015 both failed the seizure guidelines image analysis test.

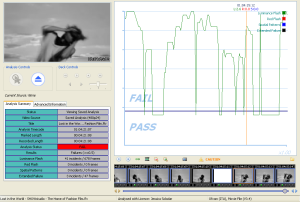

Here are the results from the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer, a tool designed to detect video images that can trigger seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy. Ironically, the video titled “Flashing Lights” passed the Harding test.

“Throughout his career, West has blended musical and visual artistry to powerful effect.” — press release announcing the Video Vanguard Award.

Removing seizure triggers doesn’t spoil the fun

Posted: 03/30/2014 Filed under: Gamers, Music Videos, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Safety modifications | Tags: computer games, flash, flicker, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games Leave a comment

A short video clip on the website of Vanderquest Limited simultaneously shows a music video both before and after changes were made for photosensitive epilepsy safety. Read on for a link to it.

Gaming fans who object to the concept of seizure-safe games have some major misconceptions about how their favorite games would look after seizure-inducing visuals are removed.

I’ve seen people in online forums threaten to stop their game subscription if the game’s images are made safe. These folks are assuming that making safety modifications to the graphics will mean “neutering” the game experience in a way that ruins their enjoyment. In fact, very minor changes to images, which can be pretty hard to detect, are often all that’s needed.

Thanks to extensive research that defined the characteristics of images that induce seizures, it’s possible to make small changes that interrupt any such seizure-generating sequences. For example, after changes are made to some video frames, the flash interval–more than 3 flashes per second–which can lead to a seizure in people with photosensitive epilepsy, no longer induces seizures.

Want some proof?

NOTE: For those with visual sensitivity, before you click on the upcoming link to side-by-side videos, know that you should be able to view the page safely because the problem images aren’t very large. If you’d prefer not to risk it, you might want to step back farther from your screen or cover the left side of your screen, because that’s where the problem images are.

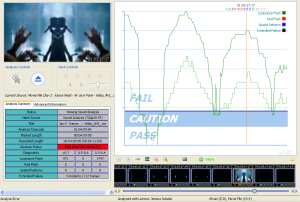

Now click to see the side-by-side images of a music video running in its original form (with safety violations) and after modifications were made to comply with seizure safety guidelines (in the UK, they’re requirements, not guidelines). The changes are very subtle! Can you find them? As you’ll see in the modified version, even visual sequences that contain some flashes and quick cuts can therefore pass the safety test. Basically, portions of some flashing sequences (9 instances) have been altered or removed, which does little to change the overall viewing experience. Edits to the video that allowed it to be broadcast were done within a single day by London-based post-production firm Vanderquest Limited.

Readers familiar with the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer that I routinely use to test video material for seizure safety will recognize the HFPA results shown beneath both versions of the music video. Although the original, uncorrected official version could not be broadcast in the UK due to regulations barring seizure-inducing material from being shown there, it lives on on YouTube.

Imagine these types of edits to the user interface of a video game. Exactly how do they ruin the gaming experience?! Or artistic expression?

David Lynch music video: 70 violations of guidelines for reducing seizures

Posted: 07/05/2013 Filed under: Music Videos, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Results of safety testing | Tags: David Lynch, flash, flicker, Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure warning, Twilight: Breaking Dawn 4 Comments

This warning is shown briefly before the video begins showing an onslaught of flashing images. This is just a screen shot, not the video itself.

David Lynch’s just-released music video for Nine Inch Nails’ “Came Back Haunted” provides more than 4 minutes of nearly constant seizure-provoking flashes and images. When analyzed for seizure safety, the video fails in 70 instances to adhere to international safety guidelines for flash, including the intermittent use of saturated red images.

Before the barrage of flashes begins, the official release on the Vevo music video website is accompanied by the following message: “WARNING: This video has been identified by Epilepsy Action to potentially trigger seizures for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Viewer discretion is advised.”

Two very big problems with this:

1. There’s a disturbing, no doubt intentional, consequence of highlighting the risk of seizures. Emphasizing that viewers are flirting with danger seems to be a marketing move. Unfortunately, this tactic does attract attention, but it trivializes the actual health risks.

2. Contrary to the claim that the UK Epilepsy Action organization determined that there was a photosensitive seizure risk in the video, Epilepsy Action’s website states that the organization was not consulted about the video. The organization is investigating and plans to continue reporting on it. A news item on the website quite correctly states, “It appears conscientious to show a warning before the video. However, many people with photosensitive epilepsy do not know they have it until something like this triggers their first seizure.” If filmmaker Lynch is conscientious, why not remove the seizure risk in the first place?

Trivializing seizures by using them for marketing

Here’s what happens when the seizure risk is used for marketing purposes. People who know nothing about epilepsy are charmed by the video’s association with seizures and use it to spice up their commentary:

- “David Lynch and Trent Reznor Make Seizure-Inducing Magic Together“ from Grantland.com

- “The New Nine Inch Nails Video Might Determine If You Have Epilepsy“ from Tucson Weekly

“…before getting into the fact it comes with a STERN WARNING THAT IT HAS BEEN KNOWN TO CAUSE SEIZURES one must take into account it was directed by David Lynch, the man responsible for Twin Peaks, Eraserhead and Blue Velvet…. I know you’ll all click on the video below to see if I’m just being outlandish and overreactive (what I like to call Glenn-Beck-ish), but remember, you were warned. Also, if you’re rendered comatose (or worse), I call dibs on your watch.”

- “Nine Inch Nails Release ‘Came Back Haunted’ Video, David Lynch’s Epileptic Nightmare“ from website of Los Angeles radio station KROQ-FM

“Came Back Haunted” packs in a myriad of flashing, distorted clips interspersed with Renzor singing as the camera captures the footage in a near-epileptic state of jitter.”

I found one reasoned commentary. Instead of swallowing the seizures-as-marketing bait, Rachel at bangs.com, to her credit, sees through it:

“…who wants to just hang out and watch a dumb boring music video anyway? I want a bit of DANGER in my viewing experience!”

Safely see for yourself how seizure-inducing it is!

I recorded what happened when I tested “Came Back Haunted” with the program I use to test images for seizure safety, the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer. If you view the testing session, you can see what it looks like when a clip is chock full of violations of seizure safety guidelines. When viewing the clip below of the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer test session, seizures are very unlikely unless you stare at the upper left-hand corner of the screen at very, very close range. (Smaller images affect a smaller area of the brain’s visual cortex, making it harder to generate the requisite number of neurons misfiring to get a seizure going.)

In this clip the video itself runs at twice its normal speed in the upper left corner of the screen. The rest of the screen shows the analyzer’s findings, in a large line graph and a table that tracks the number of frames that fail the safety test. This is not a borderline case!

Note: If you’re curious to see the offending video on YouTube in its official form, do keep in mind that since the flashing is downright nasty, the smaller you make the image on your screen, the less danger there is of triggering a seizure.

About Epilepsy Action’s role

Apart from the unauthorized and false statement that Epilepsy Action was consulted, there’s yet another problem with the claim. David Lynch is an American filmmaker, Nine Inch Nails is an American band, and the epilepsy warning refers to a British epilepsy advocacy organization that is vigilant and outspoken in monitoring photosensitive seizure triggers in popular media. Epilepsy Action has drawn the public’s attention to photosensitive seizure-provoking material in visuals broadcast on UK TV, in music videos (Kanye West) and in movies (Twilight: Breaking Dawn).

The American epilepsy advocacy community should be much more proactive and visible to the public, explaining the dangers of seizure-provoking media–including the fact that many people without “regular” epilepsy who have just photosensitive epilepsy are unaware they have the condition. If the epilepsy organizations are concerned about stigma–and they are–they need to advocate against seizure-provoking media and against demeaning portrayals of seizures that stem from photosensitivity. A whole generation of young people is forming opinions about seizures and epilepsy by reading the relentlessly insensitive stuff like David Lynch and Nine Inch Nails making “seizure-inducing magic together.”

Hat tip to John Ledford for making me aware of the video!

“Gangnam Style” is dangerously flashy

Posted: 10/12/2012 Filed under: Music Videos, Results of safety testing | Tags: flash, flicker, Gangnam Style, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, PSY, seizures Leave a commentAnother flashy music video on YouTube, and this one’s been viewed hundreds of millions of times since its July launch. The viral phenomenon “Gangnam Style” by Korean pop star PSY has lots of flash, but surprisingly, only one instance of exceeding seizure safety guidelines.

In the problem sequence, images of PSY rapidly alternate with images of another Korean performer, Kim Hyun-a. Alternating between the bright, contrasting images at a rate of 3 times per second or more creates a flash effect capable of inducing a seizure.

The wildly popular“Gangnam Style” video was followed several weeks later by the release of a female version,“Oppa Is Just My Style,” that includes more sequences with Ms. Hyun-a. The second video has considerably more flashing sequences that could easily trigger seizures in individuals with photosensitive epilepsy.

This screen grab from the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer shows a point in the video that fails the seizure safety criteria.

In the upper left of the screen grab at left (click on it to enlarge) you can see a dance sequence that is being analyzed for seizure safety. The accompanying graph indicates levels of flash (luminance) that fail to meet photosensitive epilepsy safety guidelines. Visible at the bottom of the screen are the individual frames that make up the moving sequence. The flashing effect is created by the alternating frames of bright and dark images.

How come you haven’t heard about seizures from the #1 YouTube video?

- Viewers may not maximize the video to fill the computer screen. Therefore the image is too small to affect enough neurons to cause seizures.

- Viewers are not staring continually at the screen—maybe they’re laughing, doing the horse dance, or straining to figure out the lyrics

- The seizures are happening but without many outward signs, so they are not recognized as seizures.

It’s complicated to get this regulated

Posted: 07/10/2012 Filed under: Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: 2012 Olympics logo, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, London Olympics, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizures, Ubisoft, video games Leave a comment

A promotional video for the London Olympics logo that wasn’t tested for seizure safety caused at least 30 seizures in the UK before it was pulled.

What does it take to put regulations in place that protect consumers from visually induced seizures? A lot, it turns out.

The characteristics of specific sequences and images that provoke seizures are essentially agreed upon by researchers. They have been incorporated by a UN agency–the International Telecommunication Union–into safety guidelines for flash rate, flash involving red wavelengths, and in some guidelines, high-contrast patterns. Any government, standards body, production company, game developer, or educational institution can adopt them without needing to develop expertise in photosensitive epilepsy.

The World Wide Web Consortium (WC3) is the international group that produces standards that enhance Web usability for all types of applications. Within WC3, the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) develops Web Content Acessibility Guidelines, which extend the Web’s capabilities to people with a variety of disabilities. Its Guidelines for protection of people with photosensitive seizures are based on the guidelines for flash and red flash that are now mandatory for UK television broadcasts.

I love the clear wording of Guideline 2.3: “Do not design content in a way that is known to cause seizures.”

The WCAG standards have been adopted by about a dozen countries for government, and in some cases, other public websites.

Here’s how protections have been evolving in the UK:

- In 1993 three people in the UK reported seizures from a TV commercial for Golden Wonder Pot Noodle, and the British government responded by investigating what could be done to prevent another occurrence. The television regulatory agency put broadcast guidelines in place and has subsequently refined and updated them. The regulations apply to programming and advertising. These guidelines were used in developing the ITU guidelines.

- A few years ago Parliament took up the problem of seizure-inducing video games, in response to advocacy by a mother whose son had a game seizure, and her MP. Ubisoft in theUK, which markets the game, responded by publicly committing to producing seizure-safe games. The company has produced a set of guidelines for other game developers in the UKto help them comply with safety limits.

- The British Board of Film Classification, which screens movies prior to their release to rate films for maturity of audience, requests that film makers and distributors provide warnings to audiences about any sequences that could induce photosensitive seizures. When a scene in the Twilight Breaking Dawn movie caused some seizures in the US, the Board requested that notices be placed in British movie theaters.

- When the London Olympics logo was previewed in 2007, the promotional video set off seizures in some TV viewers, resulting in a big embarrassment for the Olympics organizers.

In Japan:

- After the 1997 Pokemon incident, the government conducted a number of studies to determine the total number of children who may have experienced any symptoms from that broadcast.

- Regulation comparable to what exists in the UK was put in place for children’s television.

So, now to where things stand in the US***:

- Websites maintained by Federal agencies and their contractors are now required to comply with accessibility standards for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Amendments to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (accessibility requirements known as Section 508), which protects employment for people with disabilities, has adopted the WCAG 2.0 standards, designed to increase accessibility to people with disabilities. It’s a start, but because it applies only to federal websites, it doesn’t help the vast majority of Americans, and it certainly doesn’t help children.

- Photosensitivity protection is included in WCAG 2.0 thanks to the efforts of Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center, which provides a free tool, PEAT (Photosensitive Epilepsy Analysis Tool) that can be used by any Web authors to check material on their websites. Using PEAT, which is based on the analysis engine of the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer, authors can check that their media and websites don’t provoke seizures. It’s not for use with commercial software, though, such as games.

- The 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act was passed by Congress “to increase the access of persons with disabilities to modern communications.” Enacted in 2010, CCVA empowers the FCC to make our nation’s telecommunications equipment and services available to people with disabilities. The Coalition of Organizations for Accessible Technology was behind this legislation, with groups representing many types of disabilities pressing for their constituencies. Conspicuously absent: epilepsy advocacy groups. The inclusion of protections for people with photosensitivity was not specifically mentioned in the act. However, if the act or its implementers incorporate the Section 508/WCAG standards, or Section 255 accessibility guidelines (see Telecommunications Act of 1996, below) developed for prior telecommunications legislation, then the photosensitivity protections will apply. Otherwise, photosensitivity protection will not go anywhere without significant effort by national epilepsy organizations.

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) needs to adopt Section 508/WCAG 2.0 standards for video games played over the Internet, and broadcast and cable TV programming and advertising. Packaged software that doesn’t involve the Internet probably comes under some other agency, like the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996, governing telephone and internet service providers and telecommunications equipment including telephones, computers with modems, fax machines, etc., contains provisions in Section 255 for accessibility to people with disabilities. Section 255 includes recommendations for minimizing flicker and flash and keeping it within safe intervals.This doesn’t pertain to the content of applications, though, just underlying connectivity service.

- Is the prevention of photosensitive seizures under the jurisdiction of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention? Apparently the agency was at a meeting in 2004 regarding the possibility of regulation in the US.

When Congress has the will, that drives everything. Congress passed legislation giving a mandate to the FCC to regulate the loudness of TV commercials. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate and by a voice vote in the House! A year later (December 2011) the FCC voted unanimously to implement a set of rules prohibiting advertisers from making their commercials any louder than the actual programming. This is great–starting in mid-December when the regulations go into effect, we can all be less annoyed and our eardrums will be protected during TV advertising. Now, if we could only get some more attention paid to the public’s health when it comes to photosensitive seizures.

***My thanks to Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center for ensuring the accuracy of the above.

Kanye West loves strobe lights

Posted: 05/07/2012 Filed under: Health Consequences, Music Videos, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, Results of safety testing, Seizure Warnings | Tags: epilepsy, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure warning, seizures Leave a comment

The Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer shows flash levels in “Lost in the World” fail seizure safety guidelines by a wide margin. At upper left is a screen grab from the new video.

“Kanye West loves strobe lights,” cooed the Huffington Post the other day, reporting the release of the performer’s most recent flash-filled music video. “…the Chicago rapper…seemingly earns an epilepsy warning with every new project. His new video for the not-so-new song ‘Lost in the World’ certainly doesn’t deviate from the pattern.”

Apparently he loves strobe lights so much that–despite being informed, two music video releases ago–that his flashing visuals provoke seizures in some viewers, he is determined to use these effects anyway. Wow, you have to really respect a man who refuses to let the health of the viewing public get in the way of his artistic freedom. The Huff Post article continues in the same admiring tone: “…the rapper is known for his emphasis on quality videos (his half-hour ‘Runaway’ short film was perhaps the biggest statement of the rapper’s visual aesthetic).”

The rapper’s acknowledgement of a potential seizure problem has followed a strange path. In February 2011, accounts of seizures triggered by West’s “All of the Lights” video spurred UK-based Epilepsy Action to request that the video be removed from YouTube. In response, the video was temporarily removed and a warning was placed at the beginning:

This video has been identified by Epilepsy Action to potentially trigger seizures for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Viewer discretion is advised.

A year later the “N—-s in Paris” video was released with this same warning, although Epilepsy Action was never contacted about it.

And now there’s a warning at the beginning of the “Lost in the World” video that doesn’t even explain why the warning is important for viewers. All it says is:

Warning: Strobe effects are used in this video.

I expect Epilepsy Action will probably make a statement regarding the risks of viewing this latest release, and perhaps take issue with the less-than-explicit warning that was provided. How about some advocacy in the US? It’s time to confront the very preventable public health problem created by strobe effects in entertainment media.

Teaching about photosensitive and “regular” epilepsy together: 1+1=3

Posted: 04/17/2012 Filed under: Health Consequences, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, Protective Lenses | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, flash, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizures, TV, video games Leave a comment

Click image for 4/12/2012 editorial at epilepsy.com on including photosensitivity in epilepsy awareness campaigns.

The American epilepsy community makes information available on photosensitive seizures but in general doesn’t go out of its way to advocate for protecting consumers from visual media that can provoke seizures. Our epilepsy community doesn’t want to want to call too much attention to the risk of seizures from brightly flashing, visually overstimulating products and experiences. The priorities for public education and advocacy don’t include teaching the public about why video games contain those warnings.

But everybody wins–the “mainstream” epilepsy population, those with exclusively photosensitive seizures, and members of the public with a need to know–when epilepsy public education campaigns raise awareness of both types of epilepsy, in the context of the other.

Epilepsy doesn’t deserve its stigma and the notion that it’s an affliction exclusively of the seriously disabled. Raising awareness of epilepsy as a spectrum of seizure disorders that includes visually triggered seizures in otherwise healthy individuals could help engage the public and change misperceptions. And, much-needed photosensitivity education and advocacy can be most effectively delivered by established, well respected epilepsy organizations, as part of an overall public education program.

Here’s how I envision this:

- Part of photosensitivity education is making people aware they could already be having visually induced seizures they have never identified. People who learn about subtle, undetected seizures experienced with or without a visual trigger can seek medical assessment and treatment. People with undetected photosensitive seizures might come to understand the source of their unexplained symptoms during or shortly after being exposed to video games, TV, music videos, and other visual media.

- Those with no history of seizures and no idea they might be photosensitive would realize they should be mindful of unusual sensations and actions while exposed to lots of flash and pattern motion. Parents would be more vigilant about observing their children who are engaged in screen-based activities, and about asking them about possible symptoms of subtle seizures.

- Doctors would routinely inquire about patients’ exposure to visual media and about any unusual aftereffects, and they would recognize from patient histories when suspicion of photosensitivity is warranted.

- People who learn they have photosensitive epilepsy would know how to protect themselves and their families from triggering stimuli–through avoidance, the use of dark glasses, and limiting problem images to a small portion of the viewing field.

- The isolation and stigma endured by those with “regular” epilepsy will ease when people learn that seizures are a common disorder. The general public will understand that seizures are experienced by a broad spectrum of individuals, some who have other disabilities as well, and many who don’t. Some have seizures provoked by visual triggers, and others have seizures due to other, often unknown, triggers.

- On the strength of the advocacy of well-established epilepsy organizations, public health policy makers will become aware of the need for greater consumer protections, such as those in the UK, that require or encourage games, TV, online content, and movies to meet international guidelines for seizure-safe visual media. None of this is even under discussion in the US.

I’ve considered things from both the typical epilepsy and the exclusively-photosensitive-seizures perspectives. After discovering my daughter’s photosensitivity, we saw dramatic gains in her health and functioning after she gave up video games, her main visual trigger. But her wellness didn’t last and she went on to develop “regular” epilepsy. Daily life today is affected by unpredictable seizures and by the need to always be vigilant for visual triggers in the environment. I believe people with mainstream epilepsy–and the general public–have a tendency to assume that reflex seizures are simple to prevent and therefore the disorder is less burdensome than spontaneous seizures.

I wrote an editorial proposing that photosensitivity play a central role in a new type of awareness campaign about epilepsy. You can read “A Different Public Education Campaign” in this week’s epilepsy.com Spotlight newsletter, where I’m addressing the mainstream epilepsy community, and making the case for bringing photosensitivity under the epilepsy awareness umbrella, as it were.

A cynical Kanye West seizure warning

Posted: 02/14/2012 Filed under: Music Videos, Seizure Warnings | Tags: Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure warning, seizures 1 Comment

The video repeatedly exceeds seizure safety guidelines. Top left shows a screen grab. Graph shows multiple flash safety violations detected by the Harding Flash & Pattern Analyzer

Do Jay Z and Kanye West deserve kudos for placing a seizure warning at the start of their highly anticipated, flash-filled music video “N**gas in Paris”? Does a warning make it OK to produce videos known to place people at risk for seizures?

“Paris” is by far the most seizure-provoking piece of video I’ve ever tested with the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer. After just a few seconds it had already exceeded photosensitive seizure safety guidelines, and multiple violations continued throughout.

Because it contains a seizure warning, which was posted before anyone could complain about the seizure effects, somebody decided these guys have become considerate of those with photosensitive epilepsy. The entertainment press would like you to believe that West, who directed the video, is now sensitive to the issue of seizure-inducing images and may even have saved lives by placing a warning before the new Paris video. What a public relations coup!

“…a simple warning that Jay Z and Kanye West included at the top of their “N**gas in Paris” video may have been the difference between life and death for some of their seizure-prone fans …this according to multiple epilepsy organizations. The concern is obvious … since the video is filled with strobe lights and quick edits,” fawns TMZ.

A story headline at complex.com based on the TMZ piece reads, “CURE & Epilepsy Therapy Project Applaud Kanye West & Jay-Z for Warning in ‘Paris’ Video.” The reporter got statements from both of these highly respected US epilepsy advocacy organizations, praising the artists’ sensitivity to the epilepsy community.

Last year, when the UK’s Epilepsy Action objected to West’s very flashy “All of the Lights,” the video was temporarily removed from the Internet and subsequently reinstated with a seizure warning at the beginnning. The warning credited Epilepsy Action for determining that the video posed a seizure risk. This time around, however, without even consulting Epilepsy Action (!), the same warning was placed at the beginning of the Paris video. According to TMZ this means, “Lesson learned,” and “’Ye and Jay save the day!” Epilepsy Action, however, pointed out that while it may be good to have a warning, it would be far better if the material did not place viewers at risk of possible seizures.

Epilepsy Action notes in a statement that, “despite the concerns raised last year about the All of the Lights video, Kanye West has knowingly made another video which could be harmful to some fans watching it. We would like to see the music industry show much more responsibility by not commissioning videos that contain potentially dangerous imagery.”

The statement continues with a reminder that photosensitive seizures, especially in young people, frequently occur in individuals who don’t even know they are photosensitive. Seizure warnings are therefore totally inadequate because people incorrectly assume that if they’ve never had a visually induced seizure, they aren’t at risk. In the UK, regulations for broadcast television already require that video sequences fall within seizure safety guidelines, and Epilepsy Action is now calling for those regulations to be extended to the Internet.

Hats off once again to Epilepsy Action, and to the awareness and proactive public safety measures taken by UK communications regulators. Is anyone listening in the US and elsewhere???

Photosensitivity shares the Twilight spotlight

Posted: 11/29/2011 Filed under: Media Coverage, Movies, Seizure Warnings | Tags: computer games, epilepsy, flash, flicker, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, Twilight: Breaking Dawn, video games 1 Comment One of the biggest challenges of spreading awareness about video games causing seizures is that many video game seizures take place when people are alone. With nobody else around to witness and document these events, people assume these are very rare. Along comes a blockbuster movie with a graphic scene that triggers seizures, and photosensitive seizures are suddenly in the spotlight, as it were.

One of the biggest challenges of spreading awareness about video games causing seizures is that many video game seizures take place when people are alone. With nobody else around to witness and document these events, people assume these are very rare. Along comes a blockbuster movie with a graphic scene that triggers seizures, and photosensitive seizures are suddenly in the spotlight, as it were.

I’ve held off writing about the seizures triggered by a scene in the movie Twilight: Breaking Dawn, because I keep waiting to hear whether it’s in fact causing “epileptic seizures in filmgoers across America,” as described in the Guardian. Although the story has been picked up by many news outlets, it is based on just a handful of reported events. There are still not many people who have publicly reported seizures. (If you want to report one, you can share your experience at https://www.facebook.com/breakingdawnseizures and

https://sites.google.com/site/breakingdawnseizures/home.)

The Twilight seizures are getting widely publicized because, in addition to the high profile of the movie, the seizures that have been reported were convulsive events occurring in a crowded movie theater. A theater inDedham,Massachusettsstopped the film while the stricken viewer was given emergency assistance. In a way these people are fortunate that their sensitivity to flashing light became so evident that they can take precautions in the future. It’s possible other audience members had seizures that didn’t involve convulsions and weren’t recognized as seizures.

The birthing scene is described as graphic. In addition to the visual stress of the flashing, viewers are probably stressed by what they’re seeing. Some of the news stories remind readers of graphic scenes in other movies, such as 127 Hours provoking visceral, physical reactions in certain viewers. Stress lowers the seizure threshold, meaning that the same degree of flashing in a context that’s not so tense might not result in a seizure.

The excitement of playing video games probably has this same effect of lowering the seizure threshold. Also, while playing alone it may be easier to enter an altered state of awareness of one’s surroundings that lowers the seizure threshold. My daughter preferred to play with nobody else in the room so that she could get into a “zone” she found very pleasant. Unfortunately, once in the zone, seizures were more likely and she was less likely to have the awareness to sense them coming and prevent them by stopping or covering one eye.

I contacted the British Board of Film Classification, which screens movies prior to their release, to check for objectionable content and rate the maturity level of the content. In the UK film makers and distributors are responsible for identifying material that could provoke seizures and other adverse reactions in audiences, and provideing the appropriate warnings to audiences. If BBFC examiners notice sequences they think could affect a large number of viewers, they may require that audience warnings be added. For example, the review board noted last year that Enter the Void “includes a number of sequences of flashing and flickering lights that are likely to trigger a physical reaction in vulnerable viewers. It also contains extended sequences featuring rotating and handheld camerawork that may induce motion sickness in some viewers.”

In the UK, according to a BBFC spokesperson, no reports of Twilight: Breaking Dawn seizures have been received, nor did the BBFC identify any material likely to provoke seizures in those with light sensitivity.

Rebecca Black’s music video flickers no more

Posted: 06/20/2011 Filed under: Music Videos, Results of safety testing | Tags: computer games, Friday, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, Rebecca Black, seizures Leave a commentAfter 167 million viewings, Rebecca Black’s “Friday” music video has been pulled from YouTube because of a dispute over marketing rights. Alas, without access to the video, you can’t look for the flickering segment I wrote about in April that could cause seizures. Fortunately, I still have the video I downloaded for testing back then–when I found that it failed photosensitive seizure safety guidelines–so I can show you a still image of the segment where the problem is. The screen shot above was taken from that portion of the video, where images flash of Black, the names of the days of the week, and the song lyrics. Remember it now?

Yesterday was Thursday, Thursday

Today it is Friday, Friday

We, we, we so excited, we so excited

We gonna have a ball today

Tomorrow is Saturday

And Sunday comes afterwards…

In April I acknowledged that I hadn’t heard of anyone actually experiencing a seizure while watching the video. But since then, of all the keyword search topics that bring people to this blog, Rebecca Black’s video is #2 on the list.