Pediatricians should push for fewer seizures!

Posted: 11/17/2015 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: ADHD, American Academy of Pediatrics, autism, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a comment The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

As I’ve written previously, the AAP is rethinking its policy on media use by young children. Now it’s clear why: the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Communications and Media published new data this month on media use by very young children. According to the study, there is “almost universal exposure to mobile devices, and most had their own device by age 4.”

The media landscape has changed significantly since the AAP drafted its 2011 policy statement discouraging media use in children under age 2. Mobile ownership has increased sharply–the authors note that tablets weren’t available yet when the 2011 recommendations were written.

As part of its updated policy statement on media use, the Academy will issue revised advocacy and research objectives. How about advocating for electronic entertainment that doesn’t provoke seizures?

AAP’s current advocacy priorities on kids and media

The AAP’s Council on Communications and Media policy statement on media use from November 2013 contains a variety of advocacy recommendations, including proposals that pediatricians and the AAP:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming”

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of smoking and without product placements

Proposed changes to above initiatives

Here’s how these points should be expanded to encompass the health risk to unknown numbers of children who experience seizures from flashing visuals:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents, including the neurological impact of flashing screens

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming” – including the physiological effects of flashing and high-contrast patterns

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research that includes studies on the vulnerability of young people with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, and mood disorders

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of characters smoking and without product placements and to make video games without the flashing and pattern characteristics that can trigger seizures

Question for the AAP Council on Communications and Media

There are many angles and interests that must be considered in making your next policy statement. I have a lot to add to the conversation as far as reducing the risks to young people of screen-triggered seizures, many of which go undetected. Would you accept my assistance? I would be happy to help.

41 percent of Kanye’s videos can make you seize

Posted: 09/08/2015 Filed under: Music Videos, Results of safety testing | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures Leave a comment

Kanye West accepts the Video Vanguard Award during the 2015 MTV Video Music Awards on August 30 in Los Angeles. (Photo by Kevin Winter/MTV1415/Getty Images For MTV)

Because Kanye West received the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at last weekend’s 2015 MTV Video Music Awards, and because there were seizure risks found with some of his videos, I wanted to know how many of his music videos pose that risk. I wrote previously about a couple of his videos— All of the Lights (2011), and Lost in the World (2012)—that contain seizure-inducing images. Another one I wrote about for its seizure-inducing content, N**as in Paris (2012), was made with Jay-Z.

So in the week since Kanye was recognized for his achievement in music videos, I’ve tested as many of his music videos as I could—46—to determine how many contain flashing/moving image sequences capable of triggering seizures in sensitive individuals. My sample included only videos where Kanye is the primary performer, where he would have had artistic control over the visuals. I didn’t include those made jointly with Jay-Z or if Kanye was a featured guest on a video made by other artists.

41 percent of Kanye’s videos —that’s 19 of 46—could give you a seizure if you are vulnerable to visually induced seizures. OK, but has he stopped releasing videos that can bring on seizures? Did Kanye change his production style after UK-based Epilepsy Action called out the problem videos a few years back? Nope. The two videos I tested from 2015 both failed the seizure guidelines image analysis test.

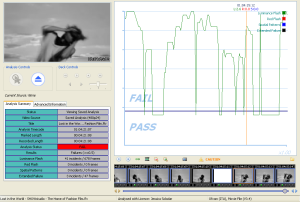

Here are the results from the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer, a tool designed to detect video images that can trigger seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy. Ironically, the video titled “Flashing Lights” passed the Harding test.

“Throughout his career, West has blended musical and visual artistry to powerful effect.” — press release announcing the Video Vanguard Award.

Epilepsy Action Tweet protects Twitterverse

Posted: 07/14/2015 Filed under: Media Coverage, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a commentFantastic what Epilepsy Action accomplished the other day with one tweet! The UK-based epilepsy advocacy group addressed a Tweet to Twitter UK asking for removal of 2 video advertisements with quickly changing colors that had the appeared as flashing images. Within an hour Twitter UK responded graciously that it had deleted the offending ads.

A major bonus–the exchange resulted in news stories in dozens of media outlets, including the Los Angeles Times, Yahoo Tech, Fortune, and the BBC News, raising awareness of the problem and showing Twitter UK as a responsive corporation.

Epilepsy Action followed up with gracious words, too:

Using the same Twitter strategy, Epilepsy Action succeeded again yesterday in getting an unsafe ad removed by media giant Virgin Media. (See Twitter exchange further down.) For some time I have been admiring Epilepsy Action’s diligence regarding photosensitive epilepsy awareness and their outreach to organizations whose products/services place the public at unnecessary risk of seizures.

Why don’t we see this kind of advocacy in the US?

- It’s not a priority of US epilepsy advocacy organizations to proactively protect the public from seizure-inducing images.

- Unlike the UK, we have no regulations barring images that could trigger seizures. In the UK both online and broadcast advertising are bound by the following rule:

“Marketers must take particular care not to include in their marketing communications visual effects or techniques that are likely to adversely affect members of the public with photosensitive epilepsy.”

- Broadcast TV in the UK is governed by a rule that, in addition to protecting against seizure-inducing content, frequently reminds the public of the risk of photosensitive seizures. No equivalent reminder exists here that raises awareness among the entire public of photosensitive epilepsy:

“Television broadcasters must take precautions to maintain a low level of risk to viewers who have photosensitive epilepsy. Where it is not reasonably practicable…and where broadcasters can demonstrate that the broadcasting of flashing lights and/or patterns is editorially justified, viewers should be given an adequate verbal and also, if appropriate, text warning at the start of the programme or programme item.”

- Because the public is often reminded of the potential for images provoking seizures, and because the government has chosen to enact regulation of moving images, it’s not an out-of-the-ordinary event for people to notice and report problem images.

Could individuals use Twitter to ask video game companies to remove potentially harmful images?

It certainly seems like something we should try. On the other hand, there are some major differences between reporting seizure-triggering online ads and bringing seizure-triggering images in a video game to the developer’s attention. For starters:

- Removing/altering problem sequences from a video game is much more technically complex than removing or fixing a seconds-long video ad from an online platform. Many popular video games are built over a period of years, using huge amounts of code, and allowing lots of variation in what images might appear onscreen, depending on how the game is played.

- An individual asking for a modification from a corporation doesn’t carry nearly the same weight as an organization such as the Epilepsy Foundation.

- Consumers’ communication about specific games typically occurs within members-only user forums that aren’t seen by the general public–thus no pressure from outside the user community.

- These user forums can be quite hostile when the topic of seizures comes up. Here’s one quote from within the gaming community.

“…(also, if you have epilepsy (knowingly), and you try to play a videogame, you don’t deserve a seizure, you deserve to be hit by a truck, and if you discover epilepsy when playing a game, that just means you have a very very sucky medical condition, its not like the game GAVE you epilepsy, just the seizure associated with your condition, its not the games fault, blame the DNA, DAMN DNA!)”

So…I will try contacting some game companies on their official Twitter page to let them know their game has failed the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer in my tests. Has anyone reading this tried to contact a video game company to report that a game triggered a seizure? I will let you know how I do!!

[Update: February 8, 2016] So I forgot to post an update. I tried tweeting 8 times to various game companies about their game having seizure-provoking images. No response…and assume that’s enough evidence to prove my point that some advocacy organization with name recognition needs to take on the issue.

Task force may look into video game seizures [updated]**

Posted: 11/27/2013 Filed under: Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy advocacy, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games 1 Comment

The Massachusetts State House in Boston, where a bill was filed to investigate video game seizures as a public health issue.

Massachusetts State Rep. Ruth Balser has filed a bill calling for a working group to examine video game seizures as a public health issue in Massachusetts. The bill has been assigned to the Joint Committee on Public Health, where Rep. Balser is a member. I had met with her a couple of years ago to share my concerns about video game seizures as an underrecognized public health problem, particularly in young people.

To date, state legislatures have considered proposals to limit access by minors to “mature” and violent game content, and one legislator in New York State has proposed that signs be posted warning of possible seizures wherever video games are sold or rented. There have been no proposals like this one in Massachusetts, where the issue of concern is the public health problem of the seizures precipitated by video games. It’s my hope that this can be investigated and discussed in a straightforward way without all the emotion that gets people so polarized whenever the game industry and its supporters are asked to respond to concerns.

The goal of this initiative is not to spoil anybody’s leisure time activities, or put game developers out of business, or take away anybody’s right to play games. It’s to reduce the risk of seizures while consumers play video games. The issue needs public discussion, and a thoughtful report prepared in the interest of public health is a good way to start.

I’m learning about the process of enacting legislation in this state. The bill was formally introduced to the Joint Committee on Public Health in September: I provided articles on photosensitive epilepsy and letters of support for the bill, and made a very brief oral statement.

The next step for the bill involves the Committee’s Director of Research, who will review the background information and support letters I provided. He will then recommend to the Committee’s House and Senate Chairs whether the bill should receive consideration by the full committee. In December, before he makes that recommendation, I will meet with him to discuss the issues and answer any questions. Stay tuned–in the coming weeks I’ll report on the progress of Mass. House bill H1892.

**3/31/14 update: There won’t be any further progress on the bill during the current legislative session (that ends at the end of the year). I’ve learned that this effort requires a lot more work than an individual can contribute…it was a valuable experience, and the door is open to file a revised version of the bill in future legislative sessions.

A game with two new champions

Posted: 11/27/2012 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, Epilepsy Foundation, Jerry Kill, Norwood Teague, University of Minnesota Gophers Leave a comment

University of Minnesota Golden Gophers, coached by Jerry Kill, play Big Ten football at the Minneapolis TCF Bank Stadium

In today’s post I’m departing from my usual focus on video games as a seizure trigger. With National Epilepsy Awareness Month coming to a close, it’s seizures in the context of the real-world game of football that recently caught my attention.

No one has done more this month than University of Minnesota football coach Jerry Kill and his athletic director Norwood Teague to educate the public about seizure disorders.

The coach had a seizure last weekend during a game against Michigan State. It was his second game-time seizure in as many months, and his third in two seasons at Minnesota. He has needed to leave the game when they happen, and in the first two instances he was admitted to a hospital. On Saturday he rested and went home to recuperate. The seizures, which Kill has experienced for years, have become more frequent, and the stresses during a game are probably adding to his seizure vulnerability. He was back at work on Monday.

The Epilepsy Foundation should publicly recognize Kill and Teague with some kind of award for doing the right thing: doing what’s necessary to carry on, taking preventive measures, and not making too big a deal about it. The players have been publicly very supportive as well.

Teague said at a post-game news conference: “I know this will bring up questions about him and moving forward, but we have 100 percent confidence in Jerry…He’s as healthy as a horse, as they say. It’s just an epileptic situation, or a seizure situation, that he deals with. He has to continue to monitor all the simple things in life, like we all do — you watch your diet, watch your weight, watch your stress, watch your rest. He just has to watch those things…You don’t want to downplay it, but you get to the point where you realize it’s just something he has to deal with at times. You don’t want to say it’s not a big deal, but in a way, it’s easy to deal with in a lot of ways.”

Yesterday Teague added that he will be looking to offload some of his coach’s responsibilities until Kill’s medical condition stabilizes. He stated this in a very positive way. “Is there doubt now about him moving forward? Absolutely not…We have to do a better job here of managing around him…I have to do a better job of helping him. I can take some things off his plate that other coaches can do.”

Kill’s condition and the way he and his management have handled it provide valuable lessons about seizure disorders. For starters, most people who have seizures:

- Are regular folks, able to live pretty normal lives during seizure-free stretches

- Aren’t unusual. About one percent of the population has epilepsy

- Aren’t looking for special treatment but may benefit from reducing stress during periods of increased seizure activity

- Can’t predict the next seizure, although certain situations–both internal and external–are triggers. (Some people experience auras beforehand.)

- Do not experience a medical emergency while seizing

- Require rest and can’t function properly for at least several hours after an episode

There’s no way to tie my thoughts on this directly back to video games and seizures. It just needed to be said.

It’s complicated to get this regulated

Posted: 07/10/2012 Filed under: Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: 2012 Olympics logo, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, London Olympics, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizures, Ubisoft, video games Leave a comment

A promotional video for the London Olympics logo that wasn’t tested for seizure safety caused at least 30 seizures in the UK before it was pulled.

What does it take to put regulations in place that protect consumers from visually induced seizures? A lot, it turns out.

The characteristics of specific sequences and images that provoke seizures are essentially agreed upon by researchers. They have been incorporated by a UN agency–the International Telecommunication Union–into safety guidelines for flash rate, flash involving red wavelengths, and in some guidelines, high-contrast patterns. Any government, standards body, production company, game developer, or educational institution can adopt them without needing to develop expertise in photosensitive epilepsy.

The World Wide Web Consortium (WC3) is the international group that produces standards that enhance Web usability for all types of applications. Within WC3, the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) develops Web Content Acessibility Guidelines, which extend the Web’s capabilities to people with a variety of disabilities. Its Guidelines for protection of people with photosensitive seizures are based on the guidelines for flash and red flash that are now mandatory for UK television broadcasts.

I love the clear wording of Guideline 2.3: “Do not design content in a way that is known to cause seizures.”

The WCAG standards have been adopted by about a dozen countries for government, and in some cases, other public websites.

Here’s how protections have been evolving in the UK:

- In 1993 three people in the UK reported seizures from a TV commercial for Golden Wonder Pot Noodle, and the British government responded by investigating what could be done to prevent another occurrence. The television regulatory agency put broadcast guidelines in place and has subsequently refined and updated them. The regulations apply to programming and advertising. These guidelines were used in developing the ITU guidelines.

- A few years ago Parliament took up the problem of seizure-inducing video games, in response to advocacy by a mother whose son had a game seizure, and her MP. Ubisoft in theUK, which markets the game, responded by publicly committing to producing seizure-safe games. The company has produced a set of guidelines for other game developers in the UKto help them comply with safety limits.

- The British Board of Film Classification, which screens movies prior to their release to rate films for maturity of audience, requests that film makers and distributors provide warnings to audiences about any sequences that could induce photosensitive seizures. When a scene in the Twilight Breaking Dawn movie caused some seizures in the US, the Board requested that notices be placed in British movie theaters.

- When the London Olympics logo was previewed in 2007, the promotional video set off seizures in some TV viewers, resulting in a big embarrassment for the Olympics organizers.

In Japan:

- After the 1997 Pokemon incident, the government conducted a number of studies to determine the total number of children who may have experienced any symptoms from that broadcast.

- Regulation comparable to what exists in the UK was put in place for children’s television.

So, now to where things stand in the US***:

- Websites maintained by Federal agencies and their contractors are now required to comply with accessibility standards for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Amendments to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (accessibility requirements known as Section 508), which protects employment for people with disabilities, has adopted the WCAG 2.0 standards, designed to increase accessibility to people with disabilities. It’s a start, but because it applies only to federal websites, it doesn’t help the vast majority of Americans, and it certainly doesn’t help children.

- Photosensitivity protection is included in WCAG 2.0 thanks to the efforts of Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center, which provides a free tool, PEAT (Photosensitive Epilepsy Analysis Tool) that can be used by any Web authors to check material on their websites. Using PEAT, which is based on the analysis engine of the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer, authors can check that their media and websites don’t provoke seizures. It’s not for use with commercial software, though, such as games.

- The 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act was passed by Congress “to increase the access of persons with disabilities to modern communications.” Enacted in 2010, CCVA empowers the FCC to make our nation’s telecommunications equipment and services available to people with disabilities. The Coalition of Organizations for Accessible Technology was behind this legislation, with groups representing many types of disabilities pressing for their constituencies. Conspicuously absent: epilepsy advocacy groups. The inclusion of protections for people with photosensitivity was not specifically mentioned in the act. However, if the act or its implementers incorporate the Section 508/WCAG standards, or Section 255 accessibility guidelines (see Telecommunications Act of 1996, below) developed for prior telecommunications legislation, then the photosensitivity protections will apply. Otherwise, photosensitivity protection will not go anywhere without significant effort by national epilepsy organizations.

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) needs to adopt Section 508/WCAG 2.0 standards for video games played over the Internet, and broadcast and cable TV programming and advertising. Packaged software that doesn’t involve the Internet probably comes under some other agency, like the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996, governing telephone and internet service providers and telecommunications equipment including telephones, computers with modems, fax machines, etc., contains provisions in Section 255 for accessibility to people with disabilities. Section 255 includes recommendations for minimizing flicker and flash and keeping it within safe intervals.This doesn’t pertain to the content of applications, though, just underlying connectivity service.

- Is the prevention of photosensitive seizures under the jurisdiction of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention? Apparently the agency was at a meeting in 2004 regarding the possibility of regulation in the US.

When Congress has the will, that drives everything. Congress passed legislation giving a mandate to the FCC to regulate the loudness of TV commercials. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate and by a voice vote in the House! A year later (December 2011) the FCC voted unanimously to implement a set of rules prohibiting advertisers from making their commercials any louder than the actual programming. This is great–starting in mid-December when the regulations go into effect, we can all be less annoyed and our eardrums will be protected during TV advertising. Now, if we could only get some more attention paid to the public’s health when it comes to photosensitive seizures.

***My thanks to Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center for ensuring the accuracy of the above.

Kanye West loves strobe lights

Posted: 05/07/2012 Filed under: Health Consequences, Music Videos, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, Results of safety testing, Seizure Warnings | Tags: epilepsy, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, Kanye West, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure warning, seizures Leave a comment

The Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer shows flash levels in “Lost in the World” fail seizure safety guidelines by a wide margin. At upper left is a screen grab from the new video.

“Kanye West loves strobe lights,” cooed the Huffington Post the other day, reporting the release of the performer’s most recent flash-filled music video. “…the Chicago rapper…seemingly earns an epilepsy warning with every new project. His new video for the not-so-new song ‘Lost in the World’ certainly doesn’t deviate from the pattern.”

Apparently he loves strobe lights so much that–despite being informed, two music video releases ago–that his flashing visuals provoke seizures in some viewers, he is determined to use these effects anyway. Wow, you have to really respect a man who refuses to let the health of the viewing public get in the way of his artistic freedom. The Huff Post article continues in the same admiring tone: “…the rapper is known for his emphasis on quality videos (his half-hour ‘Runaway’ short film was perhaps the biggest statement of the rapper’s visual aesthetic).”

The rapper’s acknowledgement of a potential seizure problem has followed a strange path. In February 2011, accounts of seizures triggered by West’s “All of the Lights” video spurred UK-based Epilepsy Action to request that the video be removed from YouTube. In response, the video was temporarily removed and a warning was placed at the beginning:

This video has been identified by Epilepsy Action to potentially trigger seizures for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Viewer discretion is advised.

A year later the “N—-s in Paris” video was released with this same warning, although Epilepsy Action was never contacted about it.

And now there’s a warning at the beginning of the “Lost in the World” video that doesn’t even explain why the warning is important for viewers. All it says is:

Warning: Strobe effects are used in this video.

I expect Epilepsy Action will probably make a statement regarding the risks of viewing this latest release, and perhaps take issue with the less-than-explicit warning that was provided. How about some advocacy in the US? It’s time to confront the very preventable public health problem created by strobe effects in entertainment media.

Teaching about photosensitive and “regular” epilepsy together: 1+1=3

Posted: 04/17/2012 Filed under: Health Consequences, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, Protective Lenses | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, flash, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizures, TV, video games Leave a comment

Click image for 4/12/2012 editorial at epilepsy.com on including photosensitivity in epilepsy awareness campaigns.

The American epilepsy community makes information available on photosensitive seizures but in general doesn’t go out of its way to advocate for protecting consumers from visual media that can provoke seizures. Our epilepsy community doesn’t want to want to call too much attention to the risk of seizures from brightly flashing, visually overstimulating products and experiences. The priorities for public education and advocacy don’t include teaching the public about why video games contain those warnings.

But everybody wins–the “mainstream” epilepsy population, those with exclusively photosensitive seizures, and members of the public with a need to know–when epilepsy public education campaigns raise awareness of both types of epilepsy, in the context of the other.

Epilepsy doesn’t deserve its stigma and the notion that it’s an affliction exclusively of the seriously disabled. Raising awareness of epilepsy as a spectrum of seizure disorders that includes visually triggered seizures in otherwise healthy individuals could help engage the public and change misperceptions. And, much-needed photosensitivity education and advocacy can be most effectively delivered by established, well respected epilepsy organizations, as part of an overall public education program.

Here’s how I envision this:

- Part of photosensitivity education is making people aware they could already be having visually induced seizures they have never identified. People who learn about subtle, undetected seizures experienced with or without a visual trigger can seek medical assessment and treatment. People with undetected photosensitive seizures might come to understand the source of their unexplained symptoms during or shortly after being exposed to video games, TV, music videos, and other visual media.

- Those with no history of seizures and no idea they might be photosensitive would realize they should be mindful of unusual sensations and actions while exposed to lots of flash and pattern motion. Parents would be more vigilant about observing their children who are engaged in screen-based activities, and about asking them about possible symptoms of subtle seizures.

- Doctors would routinely inquire about patients’ exposure to visual media and about any unusual aftereffects, and they would recognize from patient histories when suspicion of photosensitivity is warranted.

- People who learn they have photosensitive epilepsy would know how to protect themselves and their families from triggering stimuli–through avoidance, the use of dark glasses, and limiting problem images to a small portion of the viewing field.

- The isolation and stigma endured by those with “regular” epilepsy will ease when people learn that seizures are a common disorder. The general public will understand that seizures are experienced by a broad spectrum of individuals, some who have other disabilities as well, and many who don’t. Some have seizures provoked by visual triggers, and others have seizures due to other, often unknown, triggers.

- On the strength of the advocacy of well-established epilepsy organizations, public health policy makers will become aware of the need for greater consumer protections, such as those in the UK, that require or encourage games, TV, online content, and movies to meet international guidelines for seizure-safe visual media. None of this is even under discussion in the US.

I’ve considered things from both the typical epilepsy and the exclusively-photosensitive-seizures perspectives. After discovering my daughter’s photosensitivity, we saw dramatic gains in her health and functioning after she gave up video games, her main visual trigger. But her wellness didn’t last and she went on to develop “regular” epilepsy. Daily life today is affected by unpredictable seizures and by the need to always be vigilant for visual triggers in the environment. I believe people with mainstream epilepsy–and the general public–have a tendency to assume that reflex seizures are simple to prevent and therefore the disorder is less burdensome than spontaneous seizures.

I wrote an editorial proposing that photosensitivity play a central role in a new type of awareness campaign about epilepsy. You can read “A Different Public Education Campaign” in this week’s epilepsy.com Spotlight newsletter, where I’m addressing the mainstream epilepsy community, and making the case for bringing photosensitivity under the epilepsy awareness umbrella, as it were.

Photosensitive epilepsy = Purple Day epilepsy?

Posted: 03/25/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: EEG, epilepsy, epilepsy advocacy, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, Purple Day, seizures, video games Leave a commentIn 2008 an international epilepsy awareness campaign was started that designates March 26 as Purple Day. It’s a grassroots movement that provides a framework for organizing fund-raising and educational events…should people with photosensitive epilepsy be part of it? Where do visually induced seizures fit in the epilepsy world?

Somehow, photosensitive epilepsy and other reflex epilepsies, where seizures occur in response to a specific stimulus, tend not to get much notice. This is true among clinicians and the community of people with “regular” epilepsy. I can think of several factors contributing to the marginalization of photosensitive epilepsy:

1) It starts with ambivalence among the research and clinical communities as to whether photosensitive epilepsy qualifies as “real” epilepsy. The belief that this is a rare condition has a way of relegating photosensitive epilepsy to the sidelines of epilepsy research funding, advocacy, and clinical concerns. In a future post I’ll explore why the estimate of a 1-in-4,000 prevalence is tough to accept.

“…reflex epilepsy is regarded by some as a clinical curiosity and an interest such as butterfly collecting, an attractive thing of no great consequence. We are convinced that this idea is wrong…”

— Benjamin G. Zifkin, MD, co-editor of Reflex Epilepsies and Reflex Seizures (Advances in Neurology, vol. 75), from his preface to this collection of articles for neurologists. Sounds good.

But then Zifkin continues, “Although reflex epilepsy is not common, properly studied it teaches us about the brain in general and about epilepsy in particular.” (In other words, it’s not common, it’s good for studying real epilepsy.) Based on his extensive writings on the subject, I suspect Dr. Zifkin is extremely aware of the intrinsic seriousness of photosensitivity — but in the preface to his scholarly book he was appealing to the wider audience of neuroscientists who continue to view it as a trifle.

2) The manner in which seizures are defined is confusing.

Here are two quotes from the NYU Langone Medical Center website that illustrate the confusion.

- Epilepsy is a disorder in which a person has two or more unprovoked seizures.

- In reflex epilepsies, seizures are triggered or evoked by specific stimuli in the environment.

How to reconcile these? What’s the difference between provoking and triggering/evoking?

When epilepsy experts describe seizures as “unprovoked,” they are referring to seizures that are not brought on by a temporary medical situation. Unprovoked seizures are an expression of a chronic, underlying neurological condition, often not identifiable, such as a lesion or a subtle malformation in brain tissue.

“In general, seizures do not indicate epilepsy if they only occur as a result of a temporary medical condition such as high fever, low blood sugar, alcohol or drug withdrawal, or concussion. Among people who experience a seizure under such circumstances, without a history of seizures at other times, there is usually no need for ongoing treatment for epilepsy, only a need to treat the underlying medical condition.”

— Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website

If the structure and biochemical environment of the brain are such that exposure to visual stimuli such as lights and patterns brings on a seizure, this is likely a permanent condition (only 25 percent of patients outgrow photosensitivity). Therefore this kind of sensitivity should be considered a form of epilepsy. A brain tumor that causes seizures, however, is not considered to be causing epilepsy.

3) Clinicians are very conservative about assigning an epilepsy diagnosis, partly due to more liberal diagnostic practices in the past that may have exposed some patients without epilepsy to anti-epileptic drugs. Clinicians typically need conclusive EEG evidence before diagnosing epilepsy.

4) Epilepsy is still a frightening word. Most clinicians avoid it, preferring to talk about seizures. So if your seizures are triggered exclusively by a video game or strobe light, why call your sensitivity to visual stimuli by such a scary name?

5) The advocacy community remains focused on severe, life-threatening forms of epilepsy. Obtaining funding to find cures for these devastating disorders is their top priority.

So where does that leave you on March 26? Are you part of the epilepsy community or not?

2011: Inching toward fewer seizures from flashing electronic media

Posted: 01/06/2012 Filed under: Media Coverage, Medical Research, Movies, Music Videos, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, Seizure Warnings, Video Game Companies | Tags: epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, Kanye West, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizure warning, Ubisoft, video games Leave a comment A huge amount of work is needed to protect consumers from the seizures triggered by flicker and flash from screens of everyday electronic media. But in 2011 there were some notable milestones in public awareness and prevention of photosensitive seizures. In no particular order, these are the year’s top five developments:

A huge amount of work is needed to protect consumers from the seizures triggered by flicker and flash from screens of everyday electronic media. But in 2011 there were some notable milestones in public awareness and prevention of photosensitive seizures. In no particular order, these are the year’s top five developments:

- A scene in the film Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn triggered seizures in some audience members, most of whom had never experienced seizures before. Publicity about the seizures led to warnings by the UK’s Epilepsy Action and the Epilepsy Foundation of America. The film’s distributors provided a warning that cinemas could opt to provide to audiences. Although seizures triggered by movies shown in theaters aren’t common, this story brought wider attention to the risk of seizures from visual entertainment stimuli.

- Multinational game developer and distributor Ubisoft released a developers guide for creating video games that will not provoke visually induced seizures. Presumably it translates international guidelines for visual seizure safety into specific protocols for programmers. However, the guide is available only to member companies of TIGA, theUK’s trade association for video game developers and publishers.

- After the UK’s Epilepsy Action notified YouTube that an extended flashing segment in Kanye West’s music video “All of the Lights” could trigger seizures, a seizure warning was placed at the beginning of the video. It would be far better to fix than to keep the problem segments as is, even with a warning. Nobody pays attention to warnings, especially those who so far haven’t had a photosensitive seizure.

- Results of the first study to examine the rate of photosensitivity in young people on the autism spectrum were announced. They showed this population is at significantly increased risk of visually induced seizures. In young people 15 and older on the autism spectrum the photosensitivity rate is 25 percent. More studies are urgently needed, but with results as significant as these, more research will certainly be funded. While the study authors were focused more on commonalities in the roots of epilepsy and autism than on environmentally induced seizures in everyday life, the findings provide data that can be put to use immediately. The authors caution that it was too small a study (approximately 200 subjects) to merit placing limits on screen time. Nonetheless, parents of young people with autism spectrum disorders might want to be especially watchful of their children’s exposure to flashing electronic screens and any behaviors associated with screen time.

- Lenses that protect against visually induced seizures became readily commercially available. Zeiss F133 (previously known as Z1) cross-polarized, blue lenses can now be obtained from optician Antonio Bernabei, who ships worldwide from Rome. The lenses were developed by Zeiss with Italian photosensitivity researchers who demonstrated their effectiveness in clinical studies. In a study of people vulnerable to visually-induced seizures, while wearing the lenses 76 percent showed no abnormalities on EEG when tested with photic stimulation, and another 18 percent showed reduced EEG activation. Only 6 percent did not benefit at all. Until Bernabei began offering the lenses this past year, consumers and clinicians were unable to locate them without encountering a lot of dead ends.

These developments are more significant for the general public than most people realize because photosensitive seizures are not at all limited to individuals with epilepsy. Nobody knows for sure how many consumers experience visually induced seizures—including the small, unseen seizures that are never identified or reported. Three quarters of the affected people have no known history of seizures, no suspicion that they have this genetic vulnerability to flickering light, and therefore no prevention strategies. Onward to more progress in 2012!