Pediatricians should push for fewer seizures!

Posted: 11/17/2015 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: ADHD, American Academy of Pediatrics, autism, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a comment The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

As I’ve written previously, the AAP is rethinking its policy on media use by young children. Now it’s clear why: the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Communications and Media published new data this month on media use by very young children. According to the study, there is “almost universal exposure to mobile devices, and most had their own device by age 4.”

The media landscape has changed significantly since the AAP drafted its 2011 policy statement discouraging media use in children under age 2. Mobile ownership has increased sharply–the authors note that tablets weren’t available yet when the 2011 recommendations were written.

As part of its updated policy statement on media use, the Academy will issue revised advocacy and research objectives. How about advocating for electronic entertainment that doesn’t provoke seizures?

AAP’s current advocacy priorities on kids and media

The AAP’s Council on Communications and Media policy statement on media use from November 2013 contains a variety of advocacy recommendations, including proposals that pediatricians and the AAP:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming”

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of smoking and without product placements

Proposed changes to above initiatives

Here’s how these points should be expanded to encompass the health risk to unknown numbers of children who experience seizures from flashing visuals:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents, including the neurological impact of flashing screens

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming” – including the physiological effects of flashing and high-contrast patterns

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research that includes studies on the vulnerability of young people with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, and mood disorders

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of characters smoking and without product placements and to make video games without the flashing and pattern characteristics that can trigger seizures

Question for the AAP Council on Communications and Media

There are many angles and interests that must be considered in making your next policy statement. I have a lot to add to the conversation as far as reducing the risks to young people of screen-triggered seizures, many of which go undetected. Would you accept my assistance? I would be happy to help.

Reclaiming a child’s brain from video games

Posted: 08/19/2015 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: ADHD, autism, computer games, flash, flicker, neuroscience, seizures, video games Leave a comment Many parents sense that media use affects their children in vague, unseen ways. They’re not imagining it. I have an excellent book to recommend if you’d like to understand more about the way children’s brains–and therefore all aspects of daily function–are stressed by video games. Three years ago I cited a piece by child and adolescent psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley about the effects on the nervous system of interactive screen time. Dr. Dunckley outlined a syndrome of dysregulated mood, attention, executive function, and arousal that develops in response to exposure to video games and other interactive, screen-based applications.

Many parents sense that media use affects their children in vague, unseen ways. They’re not imagining it. I have an excellent book to recommend if you’d like to understand more about the way children’s brains–and therefore all aspects of daily function–are stressed by video games. Three years ago I cited a piece by child and adolescent psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley about the effects on the nervous system of interactive screen time. Dr. Dunckley outlined a syndrome of dysregulated mood, attention, executive function, and arousal that develops in response to exposure to video games and other interactive, screen-based applications.

I’m delighted that last month she published a comprehensively researched, clearly and compassionately written book explaining how interactive screens affect children’s mood, thinking, and arousal, with a lot of practical guidance on how to restore their children. In Reset Your Child’s Brain: A Four-Week Plan to End Meltdowns, Raise Grades, and Boost Social Skills by Reversing the Effects of Electronic Screen-Time, Dr. Dunckley validates parents’ concerns, pulling together research from a range of scientific fields, and in clear language explains screen-time’s effects on the nervous system.

Dr. Dunckley suggests thinking about the stress on the brain from the stimulation of electronics use as not unlike caffeine, amphetamines, or cocaine. She makes a compelling case that the nervous system’s hyperarousal (fight-or-flight response) that kicks in while playing video games sets in motion an array of biological mechanisms that lead to significant functional impairments. She says that seizure activity, along with other tangible symptoms including migraines and tics, is at the extreme end of a continuum of nervous system dysfunction due to the brain’s hyperarousal. Irritability and general nervous system dysfunction are at the other end of the continuum. Other symptoms on that spectrum include mood swings, poor executive functioning, poor impulse control, anxiety, depression, body clock disruption, and immune system suppression.

Dr. Dunckley stresses that the impairments from screen-time are not limited to screen-addicted kids or those who play violent video games, and that playing “in moderation” can still affect a child’s nervous system. Exposure tolerance varies greatly, so some children can resume limited screen use without relapses in behavior and functioning. Those with ADHD or autism spectrum disorders have a greater likelihood of becoming dysregulated by screen exposure. In general, though, the more stimulating the sensory experience, from vivid colors, rapid movements and scene changes, and multi-modal sensory input, and the more frequently the child is exposed to it, the greater the accumulated strain on the nervous system. The greater that strain, the more difficult it becomes for children to control their emotions and behavior.

“Whatever the subject manner, the style or manner in which content is delivered has its own impact. Research indicates that movement, zooms, pans, cuts, and vividness…contribute to repeated fight-or-flight reactions. Screen size affects arousal levels as well, with larger screens producing higher levels of arousal.”

On to the good news: if given respite from overstimulation, the nervous system can restore itself. Dr. Dunckley has treated hundreds of patients whose mood, behavior, and cognitive abilities have been restored after an electronic “fast,” in which electronic screens are set aside for 3 to 4 weeks for an initial evaluation period. In many cases serious limits or total abstinence from screens is necessary to sustain the remarkable improvements in daily functioning that occur. The majority of the book is devoted to practical guidance for parents on how to undertake the daunting task of disentangling a young person from daily screen use.

This book is done extremely well. It begins with a thoughtful synthesis of non-industry-funded research from widely dispersed fields, connecting the dots to show what the body’s response is to environmental stressors. Dr. Dunckley shows considerable respect for parents’ conflicted feelings and their guilt about their own screen habits:

“Let’s face it. Hearing that video games, texting, and the iPad might need to be banned from your child’s life does not fill one with glorious joy. Rather, for many, it creates an immediate urge to find a way either to discredit the information or to work around it…the inconvenience of what I’m proposing can seem overwhelming…some folks feel as though their parenting skills are being judged, or that their efforts or level of exhaustion are underappreciated.”

Dr. Dunckley provides cases from her own practice that show how life-changing the difference can be when a child’s nervous system is given a respite from electronic screens. This is serious business:

“The goal of screen limits is not merely to get rid of bothersome symptoms but to optimize a child’s development over time. All children benefit from screen limits, which have a compounded effect on functioning later in life.”

She is spot on. As some of you know, I’ve been there. Eight years ago it was a bittersweet revelation to see my daughter’s potential reemerge after a long period of impairments and health problems brought on by video game seizures. She lost several years of optimal learning, social development, and health because of frequent seizures we were unaware of during her daily video game use. We didn’t realize just how severely she’d been affected until she swore off gaming and made dramatic gains.

For the record, I don’t hate video games. But I am very disturbed that they can be so damaging to kids’ everyday functioning and potential. Read this book! Share it with your friends, too.

Note: I’ve linked to the book’s Amazon.com page so you can see the very enthusiastic reviews posted there. I am not endorsing Amazon, nor do I have a financial stake in any purchase you may decide to make.

Epilepsy Action Tweet protects Twitterverse

Posted: 07/14/2015 Filed under: Media Coverage, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a commentFantastic what Epilepsy Action accomplished the other day with one tweet! The UK-based epilepsy advocacy group addressed a Tweet to Twitter UK asking for removal of 2 video advertisements with quickly changing colors that had the appeared as flashing images. Within an hour Twitter UK responded graciously that it had deleted the offending ads.

A major bonus–the exchange resulted in news stories in dozens of media outlets, including the Los Angeles Times, Yahoo Tech, Fortune, and the BBC News, raising awareness of the problem and showing Twitter UK as a responsive corporation.

Epilepsy Action followed up with gracious words, too:

Using the same Twitter strategy, Epilepsy Action succeeded again yesterday in getting an unsafe ad removed by media giant Virgin Media. (See Twitter exchange further down.) For some time I have been admiring Epilepsy Action’s diligence regarding photosensitive epilepsy awareness and their outreach to organizations whose products/services place the public at unnecessary risk of seizures.

Why don’t we see this kind of advocacy in the US?

- It’s not a priority of US epilepsy advocacy organizations to proactively protect the public from seizure-inducing images.

- Unlike the UK, we have no regulations barring images that could trigger seizures. In the UK both online and broadcast advertising are bound by the following rule:

“Marketers must take particular care not to include in their marketing communications visual effects or techniques that are likely to adversely affect members of the public with photosensitive epilepsy.”

- Broadcast TV in the UK is governed by a rule that, in addition to protecting against seizure-inducing content, frequently reminds the public of the risk of photosensitive seizures. No equivalent reminder exists here that raises awareness among the entire public of photosensitive epilepsy:

“Television broadcasters must take precautions to maintain a low level of risk to viewers who have photosensitive epilepsy. Where it is not reasonably practicable…and where broadcasters can demonstrate that the broadcasting of flashing lights and/or patterns is editorially justified, viewers should be given an adequate verbal and also, if appropriate, text warning at the start of the programme or programme item.”

- Because the public is often reminded of the potential for images provoking seizures, and because the government has chosen to enact regulation of moving images, it’s not an out-of-the-ordinary event for people to notice and report problem images.

Could individuals use Twitter to ask video game companies to remove potentially harmful images?

It certainly seems like something we should try. On the other hand, there are some major differences between reporting seizure-triggering online ads and bringing seizure-triggering images in a video game to the developer’s attention. For starters:

- Removing/altering problem sequences from a video game is much more technically complex than removing or fixing a seconds-long video ad from an online platform. Many popular video games are built over a period of years, using huge amounts of code, and allowing lots of variation in what images might appear onscreen, depending on how the game is played.

- An individual asking for a modification from a corporation doesn’t carry nearly the same weight as an organization such as the Epilepsy Foundation.

- Consumers’ communication about specific games typically occurs within members-only user forums that aren’t seen by the general public–thus no pressure from outside the user community.

- These user forums can be quite hostile when the topic of seizures comes up. Here’s one quote from within the gaming community.

“…(also, if you have epilepsy (knowingly), and you try to play a videogame, you don’t deserve a seizure, you deserve to be hit by a truck, and if you discover epilepsy when playing a game, that just means you have a very very sucky medical condition, its not like the game GAVE you epilepsy, just the seizure associated with your condition, its not the games fault, blame the DNA, DAMN DNA!)”

So…I will try contacting some game companies on their official Twitter page to let them know their game has failed the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer in my tests. Has anyone reading this tried to contact a video game company to report that a game triggered a seizure? I will let you know how I do!!

[Update: February 8, 2016] So I forgot to post an update. I tried tweeting 8 times to various game companies about their game having seizure-provoking images. No response…and assume that’s enough evidence to prove my point that some advocacy organization with name recognition needs to take on the issue.

Game accessibility and the seizure problem

Posted: 04/23/2015 Filed under: Political Action & Advocacy, Safety modifications, Video Game Companies | Tags: computer games, Entertainment Software Association, gamers with disabilities, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a comment Momentum is growing to eliminate the barriers that make it difficult or impossible for people with disabilities to play video games. An assortment of game accessibility specialists and organizations are advocating with and educating game developers on how to adapt their offerings for gamers with physical, sensory, and/or cognitive impairments and other types of disabilities. In addition some of these organizations work with individuals to resolve specific accessibility issues.

Momentum is growing to eliminate the barriers that make it difficult or impossible for people with disabilities to play video games. An assortment of game accessibility specialists and organizations are advocating with and educating game developers on how to adapt their offerings for gamers with physical, sensory, and/or cognitive impairments and other types of disabilities. In addition some of these organizations work with individuals to resolve specific accessibility issues.

Q: How might this trend bring about progress on the seizure hazard in many games?

A: Remains to be seen because game-induced seizures don’t typically receive a lot of attention amid advocacy for other disabilities, many of which are better known.

The leading advocacy players (as it were)

There are also two well-established game accessibility groups—both founded more than 10 years ago—that address all sorts of disabilities and could therefore actively promote the development of games that are unlikely to trigger seizures.

The Able Gamers Foundation is a non-profit, staffed by volunteers, that is supported by donations from individuals and some big names in the industry, including Sony, Harmonix, the Steam storefront, and others. Able Gamers advocates for more accessible games and advises game developers on how to make necessary modifications to equipment and programs.

The organization published a set of game accessibility guidelines written by developers and by gamers with disabilities. The guidelines appear under the title Includification (I love that term). Accommodations for mobility impairments make up the largest category in the Includification booklet: remappable keys, compatibility with specialized input devices, and so on. Accommodations for hearing, vision, and cognitive disability are outlined as well. Able Gamers says that flash and flicker guidelines, not currently in the document, will be added in a revision scheduled for later this year.

Able Gamers does a lot of community outreach to gamers with special needs and tours the country demonstrating assistive technology devices that make game play possible for individuals who cannot use conventional controllers or other standard input/output technology. The group reviews games for accessibility features, and it provides online forums where disabled players can connect with each other. Able Gamers also provides grants to individuals who need customized assistive technology for gaming.

The Game Accessibility Special Interest Group (SIG) of the International Game Designers Association, founded by a member of Stockholm University’s Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, is a mix of game developers and academic and industry accessibility experts. The group presents at conferences, surveys developers, and organizes accessibility competitions for game design students. The goals of the SIG include advocacy, cross-industry cooperation, and creating a curriculum on accessible design that can be incorporated into existing post-secondary game design courses. The SIG is embarking on an ambitious, multi-faceted effort to move this agenda forward.

For developers seeking references on how to make games more accessible, the SIG recommends Able Gamers’ Includification and www.gameaccessibilityguidelines.com, a document that received an award from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The guidelines detail 100 accessibility features and include a remarkably clear outline of how to reduce the risk of flash- and pattern-induced seizures. The SIG also promotes a list of 14 accessibility features–such as easily readable closed captioning and colorblind-friendly design–that would have the most impact on gamers with disabilities. (Seizure risk reduction didn’t make the top 14 list.)

How photosensitive epilepsy is unlike other disabilities

I exchanged emails with London-based Ian Hamilton, an accessibility specialist and user experience (UX) designer active in the SIG. Hamilton was instrumental in organizing and producing gameaccessibilityguidelines.com. He respects the importance of seizure safeguards. “…even though epilepsy is relatively uncommon compared to things like colorblindness or dyslexia,” he wrote, “it’s one of the only accessibility issues that can result in physical harm, so it’s absolutely critical to get right.”

He’s absolutely right. Games and game equipment that don’t accommodate users with other disabilities typically make it frustrating or very difficult to play a satisfying game. As an example, a game lacking easily readable on-screen captioning will make users with vision or hearing impairments unhappy that they’re at a competitive disadvantage as players. But the stakes for users with photosensitive epilepsy (including the potential for serious medical issues and life-long limitations) are quite serious.

While designing images to minimize seizure risk belongs in any set of game accessibility guidelines, photosensitive epilepsy differs in some other significant ways from the other conditions/disabilities that need accommodations:

- People with photosensitive epilepsy are not a well-identified group. Many people who are at risk for image-induced seizures aren’t aware they have the condition and are therefore at risk. Either they’ve not yet been triggered or they aren’t aware of seizures they’ve already had. Since a large portion of those at risk don’t realize they need to avoid certain specific types of images, they can’t be expected to avoid those images. Game developers should therefore take some responsibility to minimize the risk of seizures.

- Advocates say many developers are responsive to specific requests for modifications that help those with a particular disability, because many accessibility issues stem from a lack of awareness by product designers of accessible design practices. Although it’s true that accessible design isn’t typically included in the game design curriculum, this argument doesn’t really hold up when it comes to seizure-inducing images. Game publishers have acknowledged for more than 20 years that their games could pose a risk to individuals with photosensitive epilepsy. The legal departments of game publishers should communicate with their own designers and developers about making games less likely to spark seizures. Many popular games continue to contain seizure-inducing images.

Just 40 percent of games recommended in the GamesBeat holiday guide complied with seizure safety guidelines.

- Advocates encourage the involvement of individuals with disabilities in the design and testing of games for the benefit of all parties. For people with visually induced seizures, this isn’t feasible, nor is it necessary. Testing needs to be done without placing people at risk, using existing analysis applications that utilize research-based image specifications. For these consumers there is little chance of developing an ongoing collaborative relationship with the industry.

- Despite a 2005 consensus paper by the Photosensitivity Task Force of the Epilepsy Foundation of America identifying seizures from visual stimulation as a significant public health problem**, there has been no organized advocacy to reduce visual stimuli in our everyday environment that can trigger seizures. Advocacy efforts (in the USA, anyway) to improve the lives of people with photosensitive epilepsy appear to be practically non-existent. In contrast, the interests of people with vision, hearing, and movement impairments are represented by organizations that proactively take on quality-of-daily-life issues.

Under the heading “Ways to further accessibility in the games industry” Ian published a comprehensive list of steps required for making video games accessible to people with disabilities. In addition to game developers and disabled gamers, the stakeholders involved would include educators in game design, game publishers and distributors, platform manufacturers, government bodies, trade groups, development tool builders, and so on. Among the recommendations: “Include basic access requirements in publisher certification requirements, such as subtitles and avoidance of common epilepsy triggers (both of these examples are required at a publisher level by Ubisoft).” Ian notes in his preface to the list that bringing about this accessibility within the game industry amounts to “wide-scale cultural change.”

Moving forward

I applaud the work of the Games Accessibility SIG, the Able Gamers Foundation, and other groups addressing accessibility. They are making strides on an important issue while faced with the task of convincing the industry that design changes for accessibility will pay off in improved overall game design and a larger customer base.

But in order to make possible the massive and broad-based cultural change that’s needed, I believe these talented and dedicated advocates need significantly greater resources, buy-in, and recognition. The industry needs to declare publicly that it is committing itself to making gaming more inclusive of people with disabilities. In the face of frequent challenges about the contents of video games and their influence on young people, the accessibility issue offers a win-win public relations opportunity for video games.

The Entertainment Software Association is just the organization to proactively announce an industry-wide goal of providing people with disabilities easier access to video game entertainment and learning. The ESA should establish and contribute major resources to a game industry consortium for promoting and achieving accessibility education, standards, learning, and collaboration, leading to a more inclusive—and larger—customer base.

** “The Photosensitivity Task Force of the Epilepsy Foundation of America believes that a seizure from visual stimulation represents a significant public health problem. No known method can eliminate all risk for a visually induced seizure in a highly susceptible person, but accumulation of knowledge about photosensitivity is now at a level sufficient to develop educational programs and procedures in the United States that substantially will reduce the risk for this type of seizure.”

— from Robert S. Fisher et al., “Photic- and Pattern-induced Seizures: A Review for the Epilepsy Foundation of America Working Group.” Epilepsia Volume 46, Issue 9 (September 2005), pages 1426–1441.

Disenfranchisement of reflex seizures ending?

Posted: 04/16/2014 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Research, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games Leave a comment

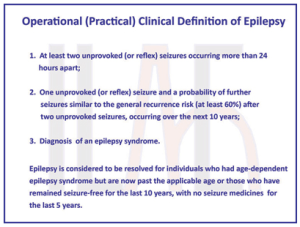

The new definition of epilepsy makes it clear that reflex seizures “count” as evidence of epilepsy. In previous definitions, this was not explicity stated.

A new definition of epilepsy published this week affirms that photosensitive and other reflex seizures qualify as “real” epilepsy. This clarification may eventually help increase awareness of seizures from video games and other electronic media.

Although reflex seizures have long been included in official classification schemes of epileptic seizures, they don’t fit cleanly into established categories of seizure types and epilepsy syndromes. In neurology training they are typically mentioned only briefly. And typically they are taken too lightly by doctors using the prevailing diagnostic criteria for epilepsy: at least two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart.

Because reflex seizures, by definition, are provoked by specific triggers, there’s confusion and most doctors have been reluctant to diagnose epilepsy in people whose epileptic seizures require an environmental provocation. The authors of the new definition paper acknowledge this:

“Under limits of the current definition, [a] patient might have photosensitive epilepsy, yet not be considered to have epilepsy because the seizures are provoked by lights…People with reflex epilepsies previously have been disenfranchised by the requirement that seizures be unprovoked. The inclusion of reflex epilepsy syndromes in a practical clinical definition of epilepsy now brings these individuals into the epilepsy community.”

Diagnostic criteria under the new definition now include at least two unprovoked or reflex seizures at least 24 hours apart. The new definition also allows an epilepsy diagnosis after a single seizure–either unprovoked or reflex–if there is a high probability of recurrence.

I’ve written previously about the inconsistency inherent in using the criterion of “unprovoked” to diagnose epilepsy in people whose seizures happen only in response to sensory triggers such as flashing light. This thinking (along with the assumption that photosensitive epilepsy is very rare) has led to marginalization of reflex seizures in the research community and among clinicians as well. Marginalization means doctors have been underdiagnosing reflex epilepsy, researchers seeking funding pursue other topics to study, and the public and public policy makers are largely unaware of the public health issue of photosensitive seizures.

The practical clinical definition was developed by a 19-member multinational task force of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), incorporating input from hundreds of other clinicians, researchers, patients, and other interested parties. I’m more than pleased that the ILAE is choosing to make it clear that reflex epilepsy deserves the same respect as other forms of the disease (the new definition paper characterizes epilepsy as a disease rather than a disorder). It’s fortunate that the chair of the ILAE task force that produced the new definition is Robert Fisher, MD, PhD of Stanford, lead author of the 2005 consensus paper describing seizures from visual stimulation as “a serious public health problem.” No doubt Dr. Fisher’s appreciation of the magnitude of the problem was instrumental in ensuring that the task force addressed it.

Not all epileptologists agree with all aspects of the new epilepsy definition–and Epilepsia has given them a voice as well, publishing half a dozen commentaries, all of which are available free online. I contributed a piece as well, providing a patient/family perspective.

Of course, it remains to be seen how long it will take for neurologists to shift their attitudes and diagnostic practices regarding reflex epilepsy. Perhaps the inclusion of reflex seizures in the epilepsy definition will help dispell the idea that reflex seizures are rare.

Task force may look into video game seizures [updated]**

Posted: 11/27/2013 Filed under: Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy advocacy, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games 1 Comment

The Massachusetts State House in Boston, where a bill was filed to investigate video game seizures as a public health issue.

Massachusetts State Rep. Ruth Balser has filed a bill calling for a working group to examine video game seizures as a public health issue in Massachusetts. The bill has been assigned to the Joint Committee on Public Health, where Rep. Balser is a member. I had met with her a couple of years ago to share my concerns about video game seizures as an underrecognized public health problem, particularly in young people.

To date, state legislatures have considered proposals to limit access by minors to “mature” and violent game content, and one legislator in New York State has proposed that signs be posted warning of possible seizures wherever video games are sold or rented. There have been no proposals like this one in Massachusetts, where the issue of concern is the public health problem of the seizures precipitated by video games. It’s my hope that this can be investigated and discussed in a straightforward way without all the emotion that gets people so polarized whenever the game industry and its supporters are asked to respond to concerns.

The goal of this initiative is not to spoil anybody’s leisure time activities, or put game developers out of business, or take away anybody’s right to play games. It’s to reduce the risk of seizures while consumers play video games. The issue needs public discussion, and a thoughtful report prepared in the interest of public health is a good way to start.

I’m learning about the process of enacting legislation in this state. The bill was formally introduced to the Joint Committee on Public Health in September: I provided articles on photosensitive epilepsy and letters of support for the bill, and made a very brief oral statement.

The next step for the bill involves the Committee’s Director of Research, who will review the background information and support letters I provided. He will then recommend to the Committee’s House and Senate Chairs whether the bill should receive consideration by the full committee. In December, before he makes that recommendation, I will meet with him to discuss the issues and answer any questions. Stay tuned–in the coming weeks I’ll report on the progress of Mass. House bill H1892.

**3/31/14 update: There won’t be any further progress on the bill during the current legislative session (that ends at the end of the year). I’ve learned that this effort requires a lot more work than an individual can contribute…it was a valuable experience, and the door is open to file a revised version of the bill in future legislative sessions.

Some doctors too reassuring about seizure risk

Posted: 08/10/2013 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Political Action & Advocacy, Seizure Risk | Tags: computer games, EEG, epilepsy, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games 3 Comments

The Howcast video, “What Is Photosensitive Epilepsy (PSE)?” is apparently designed to be upbeat and reassuring to families worried about video games.

You know how you’re not supposed to trust all the medical information on the Internet? Very true, and sometimes it’s actually the medical professionals who are placing material online that is oversimplified to the point of being misleading.

Trying to explain photosensitive epilepsy in a video of a minute and a half is pretty tough, and a Howcast clip that attempts to do that is just full of statements that make me very uncomfortable. It’s one of a series of videos on different aspects of epilepsy, but the presenters, despite their epilepsy expertise, aren’t necessarily experts in the specialty of photosensitivity. Photosensitive seizures are considered so out of the mainstream of epilepsy that few epilepsy specialists know a great deal about them.

The video in question, uploaded a year ago, features a pediatric epilepsy nurse and the Director of Pediatric Epilepsy at highly respected hospitals in New York City. My own qualifications for assessing the content of their video are found here. I’m quite certain that I’ve read more of the research on photosensitive epilepsy and seizures triggered by video games than anyone on the planet who isn’t a photosensitive epilepsy specialist. There are very, very few photosensitivity experts in the US.

This video downplays the overall prevalence/likelihood of photosensitive seizures, and it doesn’t address photosensitivity in people with no other seizures. And it overstates the conclusiveness of EEG for identifying seizure activity. Epilepsy clinicians and advocacy groups tend to want to reassure young patients and their families that in the vast majority of cases, video games and other flash-filled leisure pursuits don’t pose a seizure risk. While it’s good to encourage patients to live lives that are as normal as possible, the oversimplified message promotes the view that photosensitive epilepsy is quite rare and that doctors can know for sure, based on EEG testing, whether an individual should worry about video games as a seizure risk.

If you want to watch the video, please come back here to read my responses to what’s in it! Here’s a transcript with my comments in blue.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-Nurse: “You know, whenever anybody comes into the office, they always ask us first thing whether epilepsy can be triggered by strobe lights, and people often think back to when the first Pokemon movies came out and all those children in Japan seized during the movies. So photosensitive epilepsy is something people worry about all the time.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Two issues here:

1) Epilepsy is a condition that makes people vulnerable to seizures. It’s the seizures that are triggered; the epilepsy condition already exists. Why take issue with such a seemingly minor point? Being less than careful in how she worded things allowed a doctor in a WebMD video to incorrectly reassure viewers that video games cannot cause seizures!

2) The problem is much bigger than the population of epilepsy patients who come in to be evaluated by neurologists–people with no seizure history may develop photosensitive epilepsy (for example, the Navy pilot who can’t ever fly again after having a grand mal seizure while playing Oblivion: The Elder Scrolls IV). The general public, though–which presumably is the audience for this video–doesn’t worry enough about it. The epilepsy community should be doing more outreach to the general public to let them know they could be at risk.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Doctor: “On all the video games there’s those warnings that say, you know, you shouldn’t play this game in case you have epilepsy. But only one specific type of epilepsy has photosensitivity to it, and that’s a generalized epilepsy, that’s when the whole brain turns on all at once–”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

This is what neurologists believed in the past. But numerous studies in the last 20+ years show this is not the case. A 1994 paper that included a review of other studies concluded that about 30 percent of photosensitive seizures are partial seizures—which do not involve the whole brain. The doctor’s statement could lead viewers to think that only people with generalized (typically grand mal) seizures need to worry about photosensitivity.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Nurse:…”lights up all at once, there’s a big burst of electricity through the whole brain. It’s one of the reflex epilepsies, so kids for the most part with epilepsy can play video games and can go under strobe lights unless they very specifically seize when they’re under strobe lights, and when we do the EEGs, we do the tests of their brain waves, we actually flash lights at them to see if it does create a seizure.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The intermittent photic stimulation procedure used during EEG measures the brain’s reaction to a strobe light. The effect of a strobe light on the brain is not equal to the effect of playing a fast-moving, flashing video game. Some people who don’t respond to the strobe light can have seizures in response to video games or other visual stimuli. Studies of video game seizures frequently include individuals who experience seizures from games but do not test positive for photosensitivity. Photosensitive epilepsy in the research literature describes epileptic discharges on EEG in response to a strobe light in a laboratory. Some studies discuss non-photosensitive video game seizures: people who have the seizures even though a strobe light doesn’t produce signs of epilepsy on an EEG.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Doctor: “So by doing the EEG and flashing the lights in the child’s eyes, and having the EEG run at the same time, we can conclusively tell families whether the children can play video games or not play video games, and that will make a child very happy, hopefully finding out that it’s perfectly safe to play the video games and that they don’t have photosensitive epilepsy.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

EEG doesn’t conclusively rule out any type of seizure! It can confirm seizures but cannot rule them out since the technology does not detect all seizure activity. Some people who have seizures have normal EEGs. Oddly enough, in another video, What’s the Difference between Seizures and Epilepsy?” featuring the same clinicians in the same Howcast series, they contradict their statements in the first video, conceding that some seizures are too located too deep inside the brain to be detectable by EEG on the scalp.

7/19/2014 update: See information on a study showing just 6.2 percent of patients with visually induced seizures tested positive for photosensitivity in the photic stimulation EEG procedure.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Nurse: “As well as the teenagers and the young adults who will call or text and say, “Can I go–we’re going to a party and I know there’s going to be strobe lights. Is that OK?” So at least we have an answer for them after we’ve done the initial EEG.“

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Photosensitive epilepsy is a genetic trait that is dormant until it becomes activated by a combination of factors. The most common time for the disorder to emerge is in adolescence. Thus a child who shows no signs of photosensitivity (again, based on testing with strobe lights, not video games) may later experience photosensitive seizures.

We need epilepsy clinicians and advocacy organizations to:

- be more concerned about the many visual stimuli in our environment that can trigger seizures

- think more broadly about who may be at risk–including members of the public who have no other seizures

- convey their concern about hazardous visual stimuli to the public, the digital entertainment industry, and lawmakers

- push for public policy changes that will rein in the stimuli and reduce the occurrence of visually triggered seizures.

- question reliance on EEG and photic stimulation to diagnose vulnerability to visually induced seizures

It’s a big job. It’s a much bigger undertaking than I can even imagine, but it needs to be done.

Today the sound, tomorrow the picture?

Posted: 01/20/2013 Filed under: Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy, TV, Video Game Companies | Tags: computer games, International Telecommunication Union, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, Sony, video games 9 Comments Have you noticed that watching TV is less annoying lately? Commercials are now required to be no louder than the programming surrounding them. On December 13 an FCC regulation went into effect that was designed for just that. The CALM Act, approved by Congress in 2010, directed the Federal Communications Commission to make it possible to watch TV without constantly turning down the volume of advertisements.

Have you noticed that watching TV is less annoying lately? Commercials are now required to be no louder than the programming surrounding them. On December 13 an FCC regulation went into effect that was designed for just that. The CALM Act, approved by Congress in 2010, directed the Federal Communications Commission to make it possible to watch TV without constantly turning down the volume of advertisements.

Since the introduction of television in the 1950s, many consumers have complained to the FCC about the loudness of commercials. What prevented the FCC from doing anything in response was that the issue was technically complicated. Multiple factors can contribute to the perceived loudness of a broadcast, including the strength of the electrical signal, the degree to which the sound signal is compressed. In addition, there was no standard method for content creators and broadcasters to measure broadcast volume.

In 2006, the International Telecommunication Union–the same UN-affiliated standards body that has published specifications for protecting TV viewers from photosensitive seizures–proposed a new technique for measuring broadcast volume that allows uniform evaluation across national boundaries. In addition, the ITU proposed a numerical “target loudness” using the new loudness gauge. Thanks to the ITU, it became possible to define, comply with, and enforce limits on loudness.

Four years later the United States Congress passed the CALM Act with little debate, by unanimous vote in the Senate and by a voice vote in the House. California Congresswoman Anna Eshoo, who introduced the bill, said it was by far the most popular bill she’d ever sponsored. She said the bill “gives consumers peace of mind, because it puts them in control of the sound in their homes.” She was quoted saying, “If I’d saved 50 million children from some malady, people would not have the interest that they have in this.” By that time the UK, France, Norway, Italy, Japan, Brazil, Israel, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Poland, and the Netherlands were already limiting the loudness of commercials or had begun action on the issue.

These days even the video game industry is paying attention to some kind of audio standards, if only for consistency across products. According to an July 2012 interview in Designing Sound, Sony Computer Entertainment Europe is looking at smoothing out the volume among their own game titles.

Unfortunately, in this country making TV safer to watch for the visually sensitive–or making video games safer to play–isn’t on the legislative agenda. Consumers and policy makers aren’t aware of the need. The technical groundwork is already in place for regulations to prevent screen-induced photosensitive seizures, thanks to ITU specifications (and similar versions developed by the UK and Japan), and to similar guidelines adopted by the World Wide Web Consortium for web-based content.

Here’s where things stand at the moment in making US electronic screens safe for those with photosensitive epilepsy: Photosensitive epilepsy protection standards now apply to all federal agency websites. The Photosensitive Epilepsy Analysis Tool (PEAT) downloadable from the PACE Center at the University of Wisconsin at Madison makes available to website designers and software developers a free tool that tests screen content for compliance with seizure safety guidelines. The tool is not intended for entertainment industry developers, however; these companies need to buy commercially available assessment tools.

I’ve written previously about some of the complexities of bringing new screen safety standards to the American telecommunications industry. I”m going to learn more about the legislative process in coming months. My State Representative filed a bill last week to create a commission to study the issue of video game safety for minors at home and in school here in Massachusetts. It will take considerable time to even bring the bill to a public hearing, but as I’ve recently learned, all bills filed in the Massachusetts legislature receive a public hearing at some point in the two-year session. The two years just began this month. Stay tuned.

7 seizure triggers per hour from Spanish TV

Posted: 10/21/2012 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy, Results of safety testing, TV | Tags: photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, TV Leave a commentSpanish TV viewers are exposed to potentially seizure-inducing visual sequences about seven times per hour, according to a study released this month at the 10th European Congress on Epileptology in London. The study was led by Jaime Parra, MD, PhD, an epilepsy specialist at Madrid’s Hospital La Zarzuela and Sanatorio Nuestra Señora del Rosario.

Dr. Parra and his team recorded 105 hours of broadcasts across seven channels, capturing four consecutive hours of morning programs on five consecutive days in January. A total of 738 instances were identified where viewers were exposed to visuals that did not meet the safety guidelines for visually induced seizures. The Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer assessed flash rate, luminance (brightness), intensity of red images, and spatial patterns.

Of the 738 safety violations, 714 incidents involved bright flash. The study’s authors concluded that “Spanish broadcasters seem to be unaware of the risk of photosensitive epilepsy. National guidelines should be adopted to lower the risk of Spanish TV content triggering epileptic seizures in susceptible individuals.” The safest channel was dedicated to children’s programming. The investigators plan to bring their results to the attention of Spanish media and government officials as well as the Spanish public.

Results from the next stage of this project, which will involve analyzing the intensity of the visual stimuli that were recorded, will be presented at an upcoming meeting of the Spanish Neurological Society. The team also plans to assess television broadcasts in other European countries.

To read the poster summarizing the initial findings, click here.

It’s complicated to get this regulated

Posted: 07/10/2012 Filed under: Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: 2012 Olympics logo, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, London Olympics, music videos, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure prevention, seizures, Ubisoft, video games Leave a comment

A promotional video for the London Olympics logo that wasn’t tested for seizure safety caused at least 30 seizures in the UK before it was pulled.

What does it take to put regulations in place that protect consumers from visually induced seizures? A lot, it turns out.

The characteristics of specific sequences and images that provoke seizures are essentially agreed upon by researchers. They have been incorporated by a UN agency–the International Telecommunication Union–into safety guidelines for flash rate, flash involving red wavelengths, and in some guidelines, high-contrast patterns. Any government, standards body, production company, game developer, or educational institution can adopt them without needing to develop expertise in photosensitive epilepsy.

The World Wide Web Consortium (WC3) is the international group that produces standards that enhance Web usability for all types of applications. Within WC3, the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) develops Web Content Acessibility Guidelines, which extend the Web’s capabilities to people with a variety of disabilities. Its Guidelines for protection of people with photosensitive seizures are based on the guidelines for flash and red flash that are now mandatory for UK television broadcasts.

I love the clear wording of Guideline 2.3: “Do not design content in a way that is known to cause seizures.”

The WCAG standards have been adopted by about a dozen countries for government, and in some cases, other public websites.

Here’s how protections have been evolving in the UK:

- In 1993 three people in the UK reported seizures from a TV commercial for Golden Wonder Pot Noodle, and the British government responded by investigating what could be done to prevent another occurrence. The television regulatory agency put broadcast guidelines in place and has subsequently refined and updated them. The regulations apply to programming and advertising. These guidelines were used in developing the ITU guidelines.

- A few years ago Parliament took up the problem of seizure-inducing video games, in response to advocacy by a mother whose son had a game seizure, and her MP. Ubisoft in theUK, which markets the game, responded by publicly committing to producing seizure-safe games. The company has produced a set of guidelines for other game developers in the UKto help them comply with safety limits.

- The British Board of Film Classification, which screens movies prior to their release to rate films for maturity of audience, requests that film makers and distributors provide warnings to audiences about any sequences that could induce photosensitive seizures. When a scene in the Twilight Breaking Dawn movie caused some seizures in the US, the Board requested that notices be placed in British movie theaters.

- When the London Olympics logo was previewed in 2007, the promotional video set off seizures in some TV viewers, resulting in a big embarrassment for the Olympics organizers.

In Japan:

- After the 1997 Pokemon incident, the government conducted a number of studies to determine the total number of children who may have experienced any symptoms from that broadcast.

- Regulation comparable to what exists in the UK was put in place for children’s television.

So, now to where things stand in the US***:

- Websites maintained by Federal agencies and their contractors are now required to comply with accessibility standards for people with photosensitive epilepsy. Amendments to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (accessibility requirements known as Section 508), which protects employment for people with disabilities, has adopted the WCAG 2.0 standards, designed to increase accessibility to people with disabilities. It’s a start, but because it applies only to federal websites, it doesn’t help the vast majority of Americans, and it certainly doesn’t help children.

- Photosensitivity protection is included in WCAG 2.0 thanks to the efforts of Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center, which provides a free tool, PEAT (Photosensitive Epilepsy Analysis Tool) that can be used by any Web authors to check material on their websites. Using PEAT, which is based on the analysis engine of the Harding Flash and Pattern Analyzer, authors can check that their media and websites don’t provoke seizures. It’s not for use with commercial software, though, such as games.

- The 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act was passed by Congress “to increase the access of persons with disabilities to modern communications.” Enacted in 2010, CCVA empowers the FCC to make our nation’s telecommunications equipment and services available to people with disabilities. The Coalition of Organizations for Accessible Technology was behind this legislation, with groups representing many types of disabilities pressing for their constituencies. Conspicuously absent: epilepsy advocacy groups. The inclusion of protections for people with photosensitivity was not specifically mentioned in the act. However, if the act or its implementers incorporate the Section 508/WCAG standards, or Section 255 accessibility guidelines (see Telecommunications Act of 1996, below) developed for prior telecommunications legislation, then the photosensitivity protections will apply. Otherwise, photosensitivity protection will not go anywhere without significant effort by national epilepsy organizations.

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) needs to adopt Section 508/WCAG 2.0 standards for video games played over the Internet, and broadcast and cable TV programming and advertising. Packaged software that doesn’t involve the Internet probably comes under some other agency, like the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996, governing telephone and internet service providers and telecommunications equipment including telephones, computers with modems, fax machines, etc., contains provisions in Section 255 for accessibility to people with disabilities. Section 255 includes recommendations for minimizing flicker and flash and keeping it within safe intervals.This doesn’t pertain to the content of applications, though, just underlying connectivity service.

- Is the prevention of photosensitive seizures under the jurisdiction of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention? Apparently the agency was at a meeting in 2004 regarding the possibility of regulation in the US.

When Congress has the will, that drives everything. Congress passed legislation giving a mandate to the FCC to regulate the loudness of TV commercials. The bill passed unanimously in the Senate and by a voice vote in the House! A year later (December 2011) the FCC voted unanimously to implement a set of rules prohibiting advertisers from making their commercials any louder than the actual programming. This is great–starting in mid-December when the regulations go into effect, we can all be less annoyed and our eardrums will be protected during TV advertising. Now, if we could only get some more attention paid to the public’s health when it comes to photosensitive seizures.

***My thanks to Gregg Vanderheiden of the University of Wisconsin’s Trace Center for ensuring the accuracy of the above.