A Mind Unraveled: surviving seizures, meds, and inattentive medical care

Posted: 12/11/2018 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Care 2 Comments If you’ve ever experienced discrimination due to a medical condition, or struggled to find a clinician who could restore your health, it may be hard to maintain your composure while reading portions of Kurt Eichenwald’s riveting new memoir, A Mind Unraveled. Eichenwald, an accomplished author and journalist now at Newsweek and Vanity Fair, uses his reporting skills to chronicle the struggles of living with poorly controlled epilepsy. The book is an excellent read, particularly for anyone who’s lived with or cared for someone with epilepsy.

If you’ve ever experienced discrimination due to a medical condition, or struggled to find a clinician who could restore your health, it may be hard to maintain your composure while reading portions of Kurt Eichenwald’s riveting new memoir, A Mind Unraveled. Eichenwald, an accomplished author and journalist now at Newsweek and Vanity Fair, uses his reporting skills to chronicle the struggles of living with poorly controlled epilepsy. The book is an excellent read, particularly for anyone who’s lived with or cared for someone with epilepsy.

In addition to the disruption and anxiety caused by the seizures themselves, Eichenwald contended with inept medical care, employment and health insurance hurdles, and efforts to expel him from college because of his seizures. He describes the frightening physical and emotional experience of grand mal seizures as well as the problems that result from either disclosing his condition or hiding it. But Eichenwald details all this in the larger context of his strong resolve to live as normal and satisfying a life as possible. He mentions seizures due to flash just once (for more on this, see the last section of this post).

By candidly sharing his experiences in a compelling and well-documented story, Eichenwald has done a huge service to those with epilepsy and their families and friends. He shares his confusion, fears, anger, gratitude, and grit as well as his regrets for burdens the seizures placed on others. Spoiler alert: The author eventually found a neurologist who improved his condition. Reducing the number of seizures was possible, but only after undoing damage to his health caused by prior treatment.

Inadequate care

Finding doctors willing to engage with him and treat him as a partner in care was a challenge, especially at the onset of his epilepsy in college. When Eichenwald’s first neurologist made the epilepsy diagnosis, he offered his patient virtually no information about epilepsy or the medicine he prescribed, nor did he answer Eichenwald’s questions. Speaking with an epilepsy support counselor shortly after the diagnosis, Eichenwald’s lack of understanding of epilepsy and his treatment was evident:

The counselor mentioned grand mal seizures, and I interrupted him. “I don’t need to worry about those. My neurologist said I won’t have them anymore.”

“That’s good,” he replied, hesitation in his voice. “How did he determine that?”

“Because I’m going on the medication.”

What Eichenwald didn’t yet know, because he hadn’t been told, is that there are no guarantees for a given individual that a given anticonvulsant will be effective or that its side effects will be tolerable.

At a later point, in the care of a different neurologist, Eichenwald was hospitalized for several days for diagnostic tests. During his stay he had a grand mal seizure that nobody witnessed or asked him about, which led the hospital staff to reach conclusions without important data. Eichenwald was discharged with this assessment:

“You don’t have epilepsy. Your seizures are psychological. You’ve been here for days. You haven’t had a seizure the entire time. The most important part is your EEG. It showed no seizure activity.”

Citing normal EEGs to rule out epilepsy is a subject I’ve written about a number of times. Although EEGs do not always capture seizure activity, some doctors may point to a patient’s normal or inconclusive EEG to rule it out. While this episode clearly occurred before the introduction of video EEG allowed seizures to be captured on video, video EEG scalp electrodes are the same those used for EEG without video. With video EEG a grand mal seizure would be filmed–but subtle seizures with no outward signs could still be missed if the electrodes don’t pick up all seizure activity.

A photosensitive seizure not covered in the book

This image was sent to Eichenwald in a flashing GIF via Twitter with the intent to trigger a seizure. Upon opening the tweet, he had a grand mal seizure.

In 2016 Eichenwald had a photosensitive seizure when he opened a tweet containing a flashing GIF and the message “You deserve a seizure for your posts.” The sender was tracked down by the FBI and was charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon (the GIF).

The incident is still pending in court; that’s probably why it isn’t mentioned in the memoir. According to Eichenwald’s lawyer, the seizure left him incapacitated for several days and with no sensation in his left hand. In addition, Eichenwald had trouble speaking for several weeks afterward.

Wearable seizure detector as consumer product

Posted: 01/26/2015 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges | Tags: autism, computer games, EEG, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games, wearable computers Leave a comment

The Embrace watch doesn’t look like a medical device, but its sensor technology has been used in research published in leading neurology journals. Photo credit: Empatica

Later this year parents will be able to monitor a child’s seizure activity by using wearable technology in the form of a sleek, stylish watch with sensors underneath. The $199 Embrace watch, which will debut in October, could eventually offer a way for parents to learn whether the video games their child is playing are triggering seizures.

The Embrace won’t be able to do a thorough job of that yet—primarily because the device is currently most accurate for detecting tonic-clonic (grand mal, convulsive) seizures. Many seizures aren’t that type; they’re complex or absence, so the device would need to reliably pick up all seizure types. In addition, the Embrace hasn’t been tested specifically for picking up seizures triggered by visual stimuli. In its initial release, though, Embrace will be able to alert parents to tonic-clonic seizures while their child is asleep or in another room.

Most seizure detection devices (except EEG) rely on motion sensors that transmit an alert to a caregiver about a convulsive seizure. The Embrace wristband works primarily by detecting subtle changes in the flow of electrical charges on the skin. These changes in skin conductance are reliable indicators of changes in deep-seated areas of the brain associated with seizures, the hippocampus and amygdala. In times of cognitive, physical, or emotional arousal—and during seizures, these parts of the brain are activated. In some instances, changes on the skin can even be detected prior to the onset of a seizure.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, although EEG is the gold standard used by doctors to diagnose seizures, it’s limited in what it can pick up from structures deep inside brain. EEG uses scalp electrodes to detect electrical signals that first must penetrate the outer brain layers (cortex) and the skull. Because electrodes are affixed to the other side of these layers of tissue and bone, not all seizure signals can be detected at the surface.

The Embrace sensor technology was initially developed by the MIT Media Lab to help people on the autism spectrum to identify and communicate their stress level. The MIT team subsequently discovered that the sensors could detect not only stress/arousal levels but also seizures, including some seizures not picked up on an EEG. A start-up was formed, Empatica, to bring the wearables to market with the help of Indiegogo crowdfunding. I’m intrigued by the company’s roots in technology to aid people with autism; the autism community is probably at highest risk for photosensitive epilepsy and would therefore significantly benefit by being able to identify visually triggered seizure activity.

If your child is fatigued and kind of “out of it” at the end of a gaming session, imagine being able to find out whether hidden seizures are occurring during certain games. Wouldn’t it be great to be able to correlate seizure activity with specific video games? I’d love to see this application of the Embrace watch come about.

A video about Embrace is available on Empatica’s Indiegogo page.

Study challenges reliability of EEG test for photosensitivity

Posted: 07/19/2014 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Research | Tags: EEG, photic stimulation, photoparoxysmal response, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, video games Leave a commentIf the results of a recent study at SUNY at Buffalo are any indication, there are an awful lot of people vulnerable to visually induced seizures who are being told they aren’t at risk. The study showed that testing for photosensitivity using EEG with photic stimulation provides unreliable information. In the wake of these findings, ruling out photosensitive epilepsy–and ignoring the seizure risk from video games–simply on the basis of intermittent photic stimulation results would seem very unwise.

This study–not yet published–by the Buffalo research team found that the test is poorly correlated with vulnerability to visually induced seizures in everyday life. Just 6.2 percent of patients with a history of visually provoked seizures tested positive for photosensitivity.

The standard test for photosensitivity is intermittent photic stimulation—a strobe light flashing at specified frequencies—while hooked up to EEG. Abnormal waves provoked by the photic stimulation are known as the photoparoxysmal response (PPR). (To avoid triggering a seizure during the procedure, the flashing is halted as soon as any of these abnormal waves appear.)

Researchers have known for a long time that many people who test positive never actually experience photic seizures. The Buffalo study confirms this: of 86 patients whose EEG yielded a PPR, just 13 (15.11 percent) reported having experienced visually triggered seizures. What’s new here is the finding that many people who test negative do actually experience these seizures.

The investigators, led by Novreen Shahdad, MD, initiated their study after a patient with a clear history of seizures provoked by electronic screens did not test positive for photosensitivity. “With the increasing popularity of video games and parental concern of their predisposition for seizures,” the authors wrote, “there is a need to identify individuals at risk for PIS [photic induced seizures].”

Find the above summary on page 14 of the 2012 SUNY at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Residents Research Day program schedule

Shahdad and her colleagues examined a Buffalo EEG database and found 129 patients between 1999 and 2013 who reported seizures triggered by TV, computer use, and video games. Of those patients, a total of 8 tested positive for photosensitivity. Thirty of the 129 patients had reported a history of video game seizures. Of those 30, only one showed a photosensitive response on EEG!

Photosensitivity is defined by researchers as the appearance on EEG, in response to photic stimulation, of certain spike and wave patterns characteristic of epilepspy. Note that the criterion for photosensitivity is not the occurrence of visually induced seizures in everyday life—it refers only to the strobe test.

The study concluded:

“In contrast to the general impression, our study did not find a significant association of a positive response to photic stimulation in patients with photic induced seizures (PIS). This association was seen only in 6.2% of patients with PIS. In addition, PPR on EEG was not associated with statistically significant increase of PIS. Hence we conclude that PPR cannot be used as an isolated predictor for PIS.”

I’ve previously raised questions about diagnosing vulnerability to visually induced seizures soleley on the basis of EEG response to photic stimulation. More study is certainly warranted.

Disenfranchisement of reflex seizures ending?

Posted: 04/16/2014 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Research, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games Leave a comment

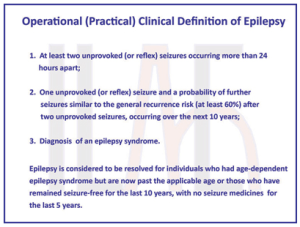

The new definition of epilepsy makes it clear that reflex seizures “count” as evidence of epilepsy. In previous definitions, this was not explicity stated.

A new definition of epilepsy published this week affirms that photosensitive and other reflex seizures qualify as “real” epilepsy. This clarification may eventually help increase awareness of seizures from video games and other electronic media.

Although reflex seizures have long been included in official classification schemes of epileptic seizures, they don’t fit cleanly into established categories of seizure types and epilepsy syndromes. In neurology training they are typically mentioned only briefly. And typically they are taken too lightly by doctors using the prevailing diagnostic criteria for epilepsy: at least two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart.

Because reflex seizures, by definition, are provoked by specific triggers, there’s confusion and most doctors have been reluctant to diagnose epilepsy in people whose epileptic seizures require an environmental provocation. The authors of the new definition paper acknowledge this:

“Under limits of the current definition, [a] patient might have photosensitive epilepsy, yet not be considered to have epilepsy because the seizures are provoked by lights…People with reflex epilepsies previously have been disenfranchised by the requirement that seizures be unprovoked. The inclusion of reflex epilepsy syndromes in a practical clinical definition of epilepsy now brings these individuals into the epilepsy community.”

Diagnostic criteria under the new definition now include at least two unprovoked or reflex seizures at least 24 hours apart. The new definition also allows an epilepsy diagnosis after a single seizure–either unprovoked or reflex–if there is a high probability of recurrence.

I’ve written previously about the inconsistency inherent in using the criterion of “unprovoked” to diagnose epilepsy in people whose seizures happen only in response to sensory triggers such as flashing light. This thinking (along with the assumption that photosensitive epilepsy is very rare) has led to marginalization of reflex seizures in the research community and among clinicians as well. Marginalization means doctors have been underdiagnosing reflex epilepsy, researchers seeking funding pursue other topics to study, and the public and public policy makers are largely unaware of the public health issue of photosensitive seizures.

The practical clinical definition was developed by a 19-member multinational task force of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), incorporating input from hundreds of other clinicians, researchers, patients, and other interested parties. I’m more than pleased that the ILAE is choosing to make it clear that reflex epilepsy deserves the same respect as other forms of the disease (the new definition paper characterizes epilepsy as a disease rather than a disorder). It’s fortunate that the chair of the ILAE task force that produced the new definition is Robert Fisher, MD, PhD of Stanford, lead author of the 2005 consensus paper describing seizures from visual stimulation as “a serious public health problem.” No doubt Dr. Fisher’s appreciation of the magnitude of the problem was instrumental in ensuring that the task force addressed it.

Not all epileptologists agree with all aspects of the new epilepsy definition–and Epilepsia has given them a voice as well, publishing half a dozen commentaries, all of which are available free online. I contributed a piece as well, providing a patient/family perspective.

Of course, it remains to be seen how long it will take for neurologists to shift their attitudes and diagnostic practices regarding reflex epilepsy. Perhaps the inclusion of reflex seizures in the epilepsy definition will help dispell the idea that reflex seizures are rare.

Some doctors too reassuring about seizure risk

Posted: 08/10/2013 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Political Action & Advocacy, Seizure Risk | Tags: computer games, EEG, epilepsy, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games 3 Comments

The Howcast video, “What Is Photosensitive Epilepsy (PSE)?” is apparently designed to be upbeat and reassuring to families worried about video games.

You know how you’re not supposed to trust all the medical information on the Internet? Very true, and sometimes it’s actually the medical professionals who are placing material online that is oversimplified to the point of being misleading.

Trying to explain photosensitive epilepsy in a video of a minute and a half is pretty tough, and a Howcast clip that attempts to do that is just full of statements that make me very uncomfortable. It’s one of a series of videos on different aspects of epilepsy, but the presenters, despite their epilepsy expertise, aren’t necessarily experts in the specialty of photosensitivity. Photosensitive seizures are considered so out of the mainstream of epilepsy that few epilepsy specialists know a great deal about them.

The video in question, uploaded a year ago, features a pediatric epilepsy nurse and the Director of Pediatric Epilepsy at highly respected hospitals in New York City. My own qualifications for assessing the content of their video are found here. I’m quite certain that I’ve read more of the research on photosensitive epilepsy and seizures triggered by video games than anyone on the planet who isn’t a photosensitive epilepsy specialist. There are very, very few photosensitivity experts in the US.

This video downplays the overall prevalence/likelihood of photosensitive seizures, and it doesn’t address photosensitivity in people with no other seizures. And it overstates the conclusiveness of EEG for identifying seizure activity. Epilepsy clinicians and advocacy groups tend to want to reassure young patients and their families that in the vast majority of cases, video games and other flash-filled leisure pursuits don’t pose a seizure risk. While it’s good to encourage patients to live lives that are as normal as possible, the oversimplified message promotes the view that photosensitive epilepsy is quite rare and that doctors can know for sure, based on EEG testing, whether an individual should worry about video games as a seizure risk.

If you want to watch the video, please come back here to read my responses to what’s in it! Here’s a transcript with my comments in blue.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-Nurse: “You know, whenever anybody comes into the office, they always ask us first thing whether epilepsy can be triggered by strobe lights, and people often think back to when the first Pokemon movies came out and all those children in Japan seized during the movies. So photosensitive epilepsy is something people worry about all the time.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Two issues here:

1) Epilepsy is a condition that makes people vulnerable to seizures. It’s the seizures that are triggered; the epilepsy condition already exists. Why take issue with such a seemingly minor point? Being less than careful in how she worded things allowed a doctor in a WebMD video to incorrectly reassure viewers that video games cannot cause seizures!

2) The problem is much bigger than the population of epilepsy patients who come in to be evaluated by neurologists–people with no seizure history may develop photosensitive epilepsy (for example, the Navy pilot who can’t ever fly again after having a grand mal seizure while playing Oblivion: The Elder Scrolls IV). The general public, though–which presumably is the audience for this video–doesn’t worry enough about it. The epilepsy community should be doing more outreach to the general public to let them know they could be at risk.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Doctor: “On all the video games there’s those warnings that say, you know, you shouldn’t play this game in case you have epilepsy. But only one specific type of epilepsy has photosensitivity to it, and that’s a generalized epilepsy, that’s when the whole brain turns on all at once–”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

This is what neurologists believed in the past. But numerous studies in the last 20+ years show this is not the case. A 1994 paper that included a review of other studies concluded that about 30 percent of photosensitive seizures are partial seizures—which do not involve the whole brain. The doctor’s statement could lead viewers to think that only people with generalized (typically grand mal) seizures need to worry about photosensitivity.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Nurse:…”lights up all at once, there’s a big burst of electricity through the whole brain. It’s one of the reflex epilepsies, so kids for the most part with epilepsy can play video games and can go under strobe lights unless they very specifically seize when they’re under strobe lights, and when we do the EEGs, we do the tests of their brain waves, we actually flash lights at them to see if it does create a seizure.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The intermittent photic stimulation procedure used during EEG measures the brain’s reaction to a strobe light. The effect of a strobe light on the brain is not equal to the effect of playing a fast-moving, flashing video game. Some people who don’t respond to the strobe light can have seizures in response to video games or other visual stimuli. Studies of video game seizures frequently include individuals who experience seizures from games but do not test positive for photosensitivity. Photosensitive epilepsy in the research literature describes epileptic discharges on EEG in response to a strobe light in a laboratory. Some studies discuss non-photosensitive video game seizures: people who have the seizures even though a strobe light doesn’t produce signs of epilepsy on an EEG.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Doctor: “So by doing the EEG and flashing the lights in the child’s eyes, and having the EEG run at the same time, we can conclusively tell families whether the children can play video games or not play video games, and that will make a child very happy, hopefully finding out that it’s perfectly safe to play the video games and that they don’t have photosensitive epilepsy.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

EEG doesn’t conclusively rule out any type of seizure! It can confirm seizures but cannot rule them out since the technology does not detect all seizure activity. Some people who have seizures have normal EEGs. Oddly enough, in another video, What’s the Difference between Seizures and Epilepsy?” featuring the same clinicians in the same Howcast series, they contradict their statements in the first video, conceding that some seizures are too located too deep inside the brain to be detectable by EEG on the scalp.

7/19/2014 update: See information on a study showing just 6.2 percent of patients with visually induced seizures tested positive for photosensitivity in the photic stimulation EEG procedure.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Nurse: “As well as the teenagers and the young adults who will call or text and say, “Can I go–we’re going to a party and I know there’s going to be strobe lights. Is that OK?” So at least we have an answer for them after we’ve done the initial EEG.“

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Photosensitive epilepsy is a genetic trait that is dormant until it becomes activated by a combination of factors. The most common time for the disorder to emerge is in adolescence. Thus a child who shows no signs of photosensitivity (again, based on testing with strobe lights, not video games) may later experience photosensitive seizures.

We need epilepsy clinicians and advocacy organizations to:

- be more concerned about the many visual stimuli in our environment that can trigger seizures

- think more broadly about who may be at risk–including members of the public who have no other seizures

- convey their concern about hazardous visual stimuli to the public, the digital entertainment industry, and lawmakers

- push for public policy changes that will rein in the stimuli and reduce the occurrence of visually triggered seizures.

- question reliance on EEG and photic stimulation to diagnose vulnerability to visually induced seizures

It’s a big job. It’s a much bigger undertaking than I can even imagine, but it needs to be done.

Signs it could have been a video game seizure

Posted: 06/11/2013 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Health Consequences, Seizure Warnings | Tags: computer games, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizure symptoms 7 Comments

My daughter Alice drew this image of what she typically saw while regaining full consciousness after a video game seizure

How can you tell you’ve had a seizure? That your child may have?

It can be easy to recognize a seizure in someone else–if the seizure involves classic convulsions. However, if you have convulsions and nobody is with you to witness the episode, when you regain awareness you probably won’t remember any part of the seizure. You might figure out that something like a seizure happened if you’d been sitting down before and don’t know how you ended up on the floor, or if you experience unexpected bruises or muscle soreness. But since the nature of most seizures is that you aren’t fully aware of your surroundings, you probably won’t know all that happened.

Non-convulsive seizures are tougher to detect in yourself or someone else, since some symptoms can be subtle and many could be attributed to other factors. Before, during and after a seizure people may experience strange sensations that are difficult to describe. Children in particular may have trouble realizing that what they’ve experienced is out of the ordinary and should be reported to a parent.

So a lot of seizures are never identified because they aren’t obvious. The most difficult seizures to identify are complex partial seizures, which elude detection but slow down your thinking, mess with your mood, and scramble your body rhythms for days afterward. And of course, some of the symptoms that follow the event itself, such as irritability, could be attributed to any number of factors.

While it would be good to know for sure if what you or your child experienced was a seizure, very often you can’t know. I’ve put together a 13 Signs You Might Have Had a Seizure While Playing a Video Game list. Consider the possibility that a seizure occurred if you notice rapid onset of any of these symptoms:

Regarding item #13, consider that sometimes you hear about people with such serious addictions to gaming that they play non-stop for many hours without a break. The common assumption is that if they wet or soiled themselves while playing, they were just too involved in the game to want to stop for a bathroom break. I think it’s much more likely that these incidents occur during the involuntary muscle movement and altered consciousness of a seizure and that the player isn’t aware of either the seizure or the mishap.

Why seizure warnings aren’t very helpful

Given the range of possible symptoms, it’s impossible for game publishers to write a meaningful seizure warning that alerts consumers to all possible symptoms. As an example, Microsoft’s photosensitive epilepsy warning—if you can find it in small print at the bottom of the Xbox Games Stores screen–says that seizures “may have a variety of symptoms, including lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness.”

If you even read the warning, that’s a lot to absorb and to keep in mind while playing. Most people aren’t looking for reasons not to go ahead and play. Nobody really wants to think photosensitive seizures could happen to them or their kids, so it isn’t until something doesn’t seem quite right that you might start trying to figure out an explanation.

What you should watch for are unusual feelings, sensations, or behavior that could indicate a seizure’s start, middle, or aftermath. Until you’ve knowingly experienced a seizure, you probably wouldn’t realize those can indicate a seizure. One clue might be if you notice the same set of symptoms happening on multiple occasions during a particular game, or in other conditions of flashing light (fireworks or flickering fluorescent bulbs, for example).

Bread and video games

Posted: 11/08/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Health Consequences, Medical Research | Tags: celiac, computer games, EEG, flash, gluten intolerance, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures 1 CommentWhat do a loaf of bread and an action video game have in common? Both are man-made and widely consumed, yet hugely underrecognized as potentially serious health hazards. There are a lot more parallels.

Sensitivity to gluten, the primary protein in wheat, and to the bright flash and rapidly moving patterns game of screens, are both considerably more pervasive than the medical community and the general public had realized. Awareness of gluten sensitivity has grown tremendously in the past decade, though, because a portion of the medical community broadened its understanding of a disorder once defined by very rigid diagnostic criteria.

Consider this comparison:

Progress on the gluten front

For decades the only type of gluten sensitivity recognized by doctors was celiac disease, a severe condition that often, but not always, manifests with gastrointestinal problems. The only diagnostic testing required an intestinal biopsy that–turns out–is easily falsely negative. After a negative biopsy, would be told that celiac disease had been ruled out, and that therefore it was OK to eat wheat and other grains containing gluten. In actuality many of these patients either had celiac–but a misleading biopsy that didn’t collect tissue samples from the affected area of the intestine–or they had a different form of gluten sensitivity that causes damage only to other body organs, rather than the intestine.

Because doctors were taught in medical school that celiac disease is very rare, occurring in only one in several thousand individuals, there seemed to be little reason to consider the diagnosis in patients, order a biopsy, or question a negative biopsy result. Some researchers suggest that ten percent or more of the American public has a sensitivity to gluten, in most cases with no obvious symptoms or symptoms that don’t suggest a food sensitivity. Even without obvious symptoms gluten intolerance can be a very serious disorder that affects daily functioning and quality of life.

Growing numbers of consumers without an official diagnosis of gluten sensitivity are being more proactive by experimenting on their own with a gluten-free diet as a healthier way to eat. Many notice a range of improvements in their well-being from this change. A rapidly expanding market of prepared gluten-free foods makes a gluten-free lifestyle less burdensome. An increasing number of restaurants offer gluten-free menus, and new gluten-free foods are a booming market for food retailers. Celiac and gluten-free support groups provide practical and moral support. In addition to peer-reviewed research, there are now a lot of books for consumers and online resources. Probably most consumers are learning about gluten sensitivity from these sources rather than their clinicians, and some are helping educate their doctors about it.

The photosensitive epilepsy front

Because doctors were taught in medical school that photosensitive epilepsy is very rare, occurring in only one in several thousand individuals, there has seemed to be little reason to consider the diagnosis in patients, order an EEG with photic stimulation, or question a negative or inconclusive EEG. There is no practical, reliable way to know how prevalent photosensitive epilepsy is in the general population. Even without obvious symptoms of a seizure, people who experience subtle seizures can experience impairments that affect daily functioning and quality of life.

Without an official diagnosis of photosensitivity, consumers can experiment with a screen-reduced or screen-free lifestyle–should they have an inkling that subtle seizure activity caused by screen exposure is affecting their health. However, at this time there are few products or supports to help them cut back on recreational screen time. A limited number of mental health providers offer therapy for Internet or video game addiction. Most focus on treating the addiction itself rather than on overcoming the physical and mental health consequences of exposure to potentially seizure-causing screens. Consumers are still essentially on their own to figure out the connection between video games and seizure activity, and there is little for them to read on the subject. Little research is being carried out in the US on photosensitivity and today’s electronic entertainment.

Perhaps there is reason to be encouraged by the progress in educating the public and clinicians about gluten-related health problems. In the face of similar obstacles to wider awareness and prevention, it should be possible for seizures induced by visually overstimulating electronic media to become better known, understood, and prevented. In the interim, a great deal of work lies ahead to empower consumers with the information they deserve about screen-induced seizures. Please help spread the word.

A continuum of visual sensitivity

Posted: 08/18/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Health Consequences, Medical Research | Tags: cartoons/animation, computer games, EEG, epilepsy, photic stimulation, photoparoxysmal response, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, SpongeBob Leave a commentIf a neurologist tells you that you don’t need to worry about seizures from electronic screen exposure, because you’re not photosensitive, what does that really mean?

It means that when you were tested for your response to a white strobe light, an EEG didn’t detect a particular abnormal electrical pattern in your brain. (I’ve noted some limitations of this procedure elsewhere.) Epileptology looks for yes or no, typically relying on EEG to rule out epilepsy. If yes, possibly medicate; if no, it’s not a case the clinician will pursue.

It does not indicate that bright flashing and/or patterns from electronic screens don’t adversely affect your brain function.

Researchers have gradually come to consensus on exactly what the EEG must look like to indicate photosensitive epilepsy (the photoparoxysmal response): certain spike/wave patterns that appear in both brain hemispheres. In arriving at these criteria, researchers excluded three other types of EEG abnormalities that in prior research “qualified” as a photoparoxysmal response. Epilepsy researchers aren’t certain what the significance of these other abnormalities is, but because the other patterns cannot conclusively be associated with epileptic seizures, there’s little interest in further research.

So these other EEG abnormalities from photic stimulation don’t count, in current neurology practice, and nobody would even tell you about them if they were found in your EEG. You’d be told the EEG was normal, period. But what if these other abnormalities were a sign that neurological function is in fact disturbed by visual stimuli, but not to the point of a seizure?

Let’s say you had one of the three other EEG abnormalities (which you wouldn’t know about, because the EEG was deemed normal). Maybe these indicate that you’re vulnerable to symptoms of a visual-overload-not-to-the-point-of-seizures syndrome. Neurologists have been examining the overlap between epilepsy, photosensitive epilepsy, and migraines. More about this in a future post, but actually there are many overlapping symptoms and correct diagnosis can be difficult. So if video game exposure or photic stimulation produces headaches and visual disturbances, and an inconclusive EEG, it may be that the visual overload is triggering migraines. Or perhaps the exposure is triggering another form of hyperexcitability in the brain’s visual cortex, which has been termed visual stress. While research has been done on this, it’s not part of a conventional neurology practice.

What about patients with more subtle or mood-related symptoms of a visual-overload-not-to-the-point-of-seizures problem? Who is treating these patients? Could be psychiatrists and psychologists, who view altered behavior and cognitive function through the lens of their respective training. Because there’s such a dearth of research of the gray areas of brain dysfunction following exposure to electronic screens, mental health providers have no basis for treating these patients for anything but mental health disorders. It’s clear that more research is needed and that more effects on the brain will be uncovered. One intriguing paper explores the contribution of fluorescent lighting to agoraphobia. The SpongeBob study published last year showed diminished executive function in children who viewed the cartoon.

In her Psychology Today blog, psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley recently posted a compelling piece about the effects on her patients of electronic screen time. She recommends creating a diagnostic category called Electronic Screen Syndrome to identify a dysregulation of mood, attention, or arousal level due to overstimulation of the nervous system by electronic screen media. She has seen dramatic improvements in hundreds of patients’ mood, behavior, and cognition after they go on an “electronic fast.” (Some have underlying psychiatric diagnoses, some don’t.) Maybe these patients were having very subtle seizures from electronic screens. Maybe the effects on the nervous system weren’t quite what epileptology defines as seizures. Either way, many kids exposed to electronic screens are experiencing diminished quality of life (as are their families) for a problem that medicine has not yet acknowledged.

Photosensitive epilepsy = Purple Day epilepsy?

Posted: 03/25/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: EEG, epilepsy, epilepsy advocacy, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, Purple Day, seizures, video games Leave a commentIn 2008 an international epilepsy awareness campaign was started that designates March 26 as Purple Day. It’s a grassroots movement that provides a framework for organizing fund-raising and educational events…should people with photosensitive epilepsy be part of it? Where do visually induced seizures fit in the epilepsy world?

Somehow, photosensitive epilepsy and other reflex epilepsies, where seizures occur in response to a specific stimulus, tend not to get much notice. This is true among clinicians and the community of people with “regular” epilepsy. I can think of several factors contributing to the marginalization of photosensitive epilepsy:

1) It starts with ambivalence among the research and clinical communities as to whether photosensitive epilepsy qualifies as “real” epilepsy. The belief that this is a rare condition has a way of relegating photosensitive epilepsy to the sidelines of epilepsy research funding, advocacy, and clinical concerns. In a future post I’ll explore why the estimate of a 1-in-4,000 prevalence is tough to accept.

“…reflex epilepsy is regarded by some as a clinical curiosity and an interest such as butterfly collecting, an attractive thing of no great consequence. We are convinced that this idea is wrong…”

— Benjamin G. Zifkin, MD, co-editor of Reflex Epilepsies and Reflex Seizures (Advances in Neurology, vol. 75), from his preface to this collection of articles for neurologists. Sounds good.

But then Zifkin continues, “Although reflex epilepsy is not common, properly studied it teaches us about the brain in general and about epilepsy in particular.” (In other words, it’s not common, it’s good for studying real epilepsy.) Based on his extensive writings on the subject, I suspect Dr. Zifkin is extremely aware of the intrinsic seriousness of photosensitivity — but in the preface to his scholarly book he was appealing to the wider audience of neuroscientists who continue to view it as a trifle.

2) The manner in which seizures are defined is confusing.

Here are two quotes from the NYU Langone Medical Center website that illustrate the confusion.

- Epilepsy is a disorder in which a person has two or more unprovoked seizures.

- In reflex epilepsies, seizures are triggered or evoked by specific stimuli in the environment.

How to reconcile these? What’s the difference between provoking and triggering/evoking?

When epilepsy experts describe seizures as “unprovoked,” they are referring to seizures that are not brought on by a temporary medical situation. Unprovoked seizures are an expression of a chronic, underlying neurological condition, often not identifiable, such as a lesion or a subtle malformation in brain tissue.

“In general, seizures do not indicate epilepsy if they only occur as a result of a temporary medical condition such as high fever, low blood sugar, alcohol or drug withdrawal, or concussion. Among people who experience a seizure under such circumstances, without a history of seizures at other times, there is usually no need for ongoing treatment for epilepsy, only a need to treat the underlying medical condition.”

— Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website

If the structure and biochemical environment of the brain are such that exposure to visual stimuli such as lights and patterns brings on a seizure, this is likely a permanent condition (only 25 percent of patients outgrow photosensitivity). Therefore this kind of sensitivity should be considered a form of epilepsy. A brain tumor that causes seizures, however, is not considered to be causing epilepsy.

3) Clinicians are very conservative about assigning an epilepsy diagnosis, partly due to more liberal diagnostic practices in the past that may have exposed some patients without epilepsy to anti-epileptic drugs. Clinicians typically need conclusive EEG evidence before diagnosing epilepsy.

4) Epilepsy is still a frightening word. Most clinicians avoid it, preferring to talk about seizures. So if your seizures are triggered exclusively by a video game or strobe light, why call your sensitivity to visual stimuli by such a scary name?

5) The advocacy community remains focused on severe, life-threatening forms of epilepsy. Obtaining funding to find cures for these devastating disorders is their top priority.

So where does that leave you on March 26? Are you part of the epilepsy community or not?

Would you know if you just had a seizure?

Posted: 01/28/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Health Consequences | Tags: computer games, EEG, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, Twilight: Breaking Dawn, video games 24 Comments No, not necessarily. You might have no idea it happened, even. Multiple studies have shown that people often aren’t aware of their own seizures. When you consider that altered consciousness is characteristic of many seizures, it’s not so surprising. People who aren’t “all there” during the seizure may have no memory of it.

No, not necessarily. You might have no idea it happened, even. Multiple studies have shown that people often aren’t aware of their own seizures. When you consider that altered consciousness is characteristic of many seizures, it’s not so surprising. People who aren’t “all there” during the seizure may have no memory of it.

And if you have a seizure with subtle symptoms, anyone who’s with you may not realize it’s happening, either. This is a key reason many people haven’t heard much about video game seizures–many just go undetected.

The big seizures, of course, get noticed. Anyone nearby can clearly see a person who has fallen and is having convulsions. Individuals emerging from a grand mal seizure (what doctors now refer to as a tonic-clonic seizure) won’t remember the event itself, but will realize they’re not where they were before (perhaps finding themselves on the floor or in an ambulance), and may have bruises from uncontrolled movements.

Although studies show that photosensitive epilepsy can cause any type of seizure, a lot of clinicians still assume the condition produces only grand mal/tonic-clonic seizures. They may not know that partial and absence seizures are associated with photosensitivity, too. Click here for a list of some typical signs you may have had a seizure.

What are partial and absence seizures?

Partial and absence seizures can act like stealth attacks on the brain. They cause unusual behaviors and sensations, and may be followed by additional symptoms, but they often escape notice while the seizure is in progress.

Simple partial seizures produce temporary symptoms such as distorted vision or unexpected movement or tingling in one limb. Because they affect a small area of the brain, awareness and memory are not affected.

Complex partial seizures occur in 35 percent of people with seizures. Many types of behavior can take place during the seizure, depending on which parts of the brain are affected. Sometimes people may seem to continue whatever they had been doing, including talking with others. Sometimes during one of these events people are conscious enough to allow them to hear what’s going on around them–perhaps feeling everything is happening far away–but they aren’t able to speak. Because consciousness is altered, it’s not uncommon to have either no memory of what happened during the seizure or just a vague idea. The event can be over in 30 seconds, or it may last for a few minutes.

The seizures are typically followed by headache, temporary confusion, memory loss, and/or other neurological dysfunction, as well as fatigue and “brain fog” that gradually dissipate over a period lasting up to a few days. Lingering after-effects of complex partials can easily be more of a disruption to everyday life than the seizures themselves.

Absence seizures, where a person briefly stares and “zones out,” may be very hard to notice and can be mistaken for attention problems. Learning, memory, and social interaction are often affected by the gaps resulting from interruptions in awareness, but absence seizures are not followed by after-effects.

Research shows people often don’t detect their own seizures

In a study published in 2007 by Christian Hoppe and colleagues, 91 seizure patients were asked to record all of their seizures in a diary during the time they were being monitored on EEG. In instances where patients activated a reporting alarm just prior to or during a seizure, only two-thirds of the seizures were documented afterwards by the patients. The reliability of patient reporting was lowest when documenting complex partial seizures and seizures experienced during sleep. Of 150 complex partial seizures (verified on EEG) while subjects were awake, only 52.7 percent of the events were reported, even though subjects were periodically reminded to report all their seizures.

The study authors state, “Seizure-induced seizure unawareness is a frequent, but rather unrecognized, postictal [post-seizure] symptom particularly associated with seizures from sleeping and with CPS [complex partial seizures].” Now consider, what are the chances that a person who has never had a seizure before, or whose seizures have never been identified, will remember after the event that something unusual happened?

In the 2004 review article “Visual Stimuli in Daily Life,” Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité and colleagues note that during photic stimulation testing many patients do not notice brief seizures that are detected on the EEG but have no clinical signs. “The question must be raised,” they continue, “whether asymptomatic individuals might have unnoticed reflex seizures triggered by daily-life stimuli and become overtly symptomatic only when a critical age is reached (early adolescence), in combination with lifestyle-related factors.” In other words, after adolescence, photosensitive seizures that were already happening but nobody was aware of may become more visible, possibly when the nervous system is affected by additional circumstances (lack of sleep, alcohol consumption, etc.).

Need more data? In a 1996 study of 27 seizure patients by Blum and colleagues, patients were not aware of 61 percent of their seizures detected on EEG! Seven patients didn’t recall any of their seizures. Patients were questioned periodically throughout the day as to whether they’d had a seizure or if anything unusual had occurred, so the seizures would be expected to be fresh in their minds.

Can an EEG help determine whether you had a seizure?

Let’s say something suddenly felt very weird yesterday, and you’re wondering if it was a seizure. An EEG conducted today can’t tell you if yesterday’s event was a seizure. That’s because EEGs can’t provide data on any period other than the time the electrodes are in place and recording brain activity. An initial EEG usually lasts for 20 to 30 minutes and can be thought of as an extended “snapshot” of brain wave patterns. If you have a seizure during an EEG, the EEG can confirm that it was a seizure–but only if electrodes pick up the brain waves that typically signify a seizure.

Usually at some point during the EEG you’re exposed to a strobe light to see if your brain has an abnormal response to flash. If that part of the EEG is abnormal, it can indicate that you have photosensitive epilepsy and should avoid flashing lights. The test is done in a way that doesn’t provoke an actual seizure, but it can show an abnormal “firing” of neurons that is consistent with seizures. Note that strobe lights may not create that EEG response even if a video game does–the flashing white light doesn’t make the same impact on the visual cortex that a colorful screen with lots of action. Some people don’t respond to the strobe but do have an abnormal EEG response to certain sharply defined patterns. Video games and TV may include some of these patterns, but little testing is done for pattern sensitivity in the US.

EEGs done with scalp electrodes miss a lot of seizure activity that involves a small area and/or lies deep inside the brain, far from electrodes on the surface. I’ve written about this before, but I can’t resist adding that this point was acknowledged in the above study by Blum et al. “…there are seizure types that often do not manifest on surface EEG. The most important of these is frontal lobe epilepsy, but this also occurs with complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin.”

In fact, “it is crucial to recognize that a normal EEG does not exclude epilepsy, as around 10% of patients with epilepsy never show epileptiform discharges,” according to a 2005 paper in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgury & Psychiatry.

Seizures are more common and frequent than current technology and human memory can demonstrate.