Safe to play a game that passes the seizure test?

Posted: 01/17/2016 Filed under: Medical Research, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Results of safety testing, Seizure Risk, TV | Tags: computer games, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games 4 Comments

Until now I’ve posted charts in this format to show whether a game meets photosensitive epilepsy guidelines…

According to a Reddit post, a game that I’ve said “passed the seizure test” triggered a seizure. Recently the same game—Hearthstone—could have been implicated in a professional gamer’s seizure that happened during a live stream. What’s going on?

I write about games I’ve tested to alert readers to the games that don’t meet internationally recognized image safety guidelines. But I don’t want to create undeserved confidence that a game that passed the seizure test will be safe for anyone with photosensitive epilepsy.

Ian Hamilton, a user interface designer who specializes in and advocates for game accessibility, clarifies the role of testing this way:

“Passing the Harding test doesn’t mean that a game is safe. It means ‘reasonably safe’ because common triggers have been avoided. Something that gets a ‘pass’ can still absolutely cause seizures.”

I regularly write that your experience may differ, that I’m not trained in quality assurance, that I test excerpts of game play, and that health and lifestyle variables affect every individual’s vulnerability to seizures at any given time. Still, the meaning of my findings could be misleading without an understanding of the limitations of the seizure test itself:

- the pass/fail guidelines aren’t expected to prevent seizures in all individuals

- the test was designed for TV images, not video games

What the Pass/Fail guidelines mean

The guidelines originated in 1994, when the UK’s agency for regulating TV broadcasting (now known as Ofcom) inserted into its code of standards some technical guidelines to accommodate viewers with photosensitive epilepsy. These guidelines, based on studies of photosensitive epilepsy and consultation with Prof. Graham Harding and other photosensitive epilepsy experts, detail flash rates and spatial patterns that typically trigger seizures in people with photosensitive epilepsy. Specifications regarding saturated red images were added later, after the 1997 Pokémon incident in Japan.

Some compromises in the guidelines were made for the sake of practicality. Criteria for acceptable images (commonly referred to as the Harding test) were developed with the understanding that they would realistically protect most individuals with photosensitive epilepsy, but not all. For example, the guidelines permit images that flash at a rate of up to 3 times per second because flash at that frequency affects only 3 percent of photosensitive individuals. UK regulators decided that was “an acceptably small risk.”

…but I’m updating all the charts by removing the word “safety” since passing the test doesn’t guarantee seizure safety.

The introduction to the guidelines states that their purpose is “reducing the risk of exposure to potentially harmful stimuli.” It also concedes that even when broadcasting images that comply with the guidelines,

“it is…impossible to eliminate the risk of television causing convulsions in viewers with photosensitive epilepsy.”

Applying TV guidelines to video games

There are no formal guidelines for reducing the seizure risk from video games. A 2005 consensus paper by experts on photosensitive seizures acknowledges that additional work would be required first on the existing guidelines for TV. In the meantime, it is reasonable to use the television guidelines since the impact of screen images on the visual system is the same.

The biggest challenge in applying TV specifications to video games is explained in the consensus paper:

“These principles are easier to apply in the case of fixed media (for example, a prerecorded TV show), which can be analyzed frame-by-frame. Interactive media, such as video games, may afford essentially limitless pathways through the game, depending on user actions. Therefore …in the case of video games, the consensus recommendations apply to typical pathways of play but cannot cover every eventuality of play.”**

Reducing risk going forward

In sum, a game that fails the Harding test is best avoided by those with photosensitive epilepsy. A game that passes is less likely to act as a trigger. Despite all the qualifiers, I believe there’s value in reminding people that seizures can happen to anybody, that certain video games can trigger them, and that you can lessen the risk by selecting games without lots of flash and patterns. Other strategies to lessen the risk of photosensitive seizures can be found here and here.

Tip of the hat to Ian, who suggested that I avoid the word “safe” when describing games that have passed the test. I also will be revising my prior posts to do some rewording.

Gamer’s seizure on live stream

Here’s a reminder that seizures can happen to anyone. A professional gamer known as Lothar had a seizure recently during his live feed while playing Hearthstone on Twitch. Lothar apparently has no history of seizures and the seizure may or may not have any connection to Hearthstone. In updates about his condition and hospital stay, Lothar didn’t mention photosensitive epilepsy nor has he said he’s been advised to limit his gameplay.

For the record, Lothar is also a body builder—he’s obviously a guy who has enjoyed good health and takes good care of himself. Lothar has a large and caring following and has been receiving lots of well wishes as he recovers. Why do I mention this incident here? Viewing the incident (you can find it on YouTube) and seeing how it affected so many fans who care about him reinforced for me the seriousness of seizures and the importance of preventing those that are preventable.

Pediatricians should push for fewer seizures!

Posted: 11/17/2015 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: ADHD, American Academy of Pediatrics, autism, computer games, epilepsy advocacy, flash, flicker, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a comment The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

The pediatricians of this country, working with the American Academy of Pediatrics, are in a position to help reduce the continuing public health risk of video games and other media that can induce seizures. They should lobby the entertainment industry — something they already apparently do regarding other media matters — to produce games without seizure-inducing images.

As I’ve written previously, the AAP is rethinking its policy on media use by young children. Now it’s clear why: the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Communications and Media published new data this month on media use by very young children. According to the study, there is “almost universal exposure to mobile devices, and most had their own device by age 4.”

The media landscape has changed significantly since the AAP drafted its 2011 policy statement discouraging media use in children under age 2. Mobile ownership has increased sharply–the authors note that tablets weren’t available yet when the 2011 recommendations were written.

As part of its updated policy statement on media use, the Academy will issue revised advocacy and research objectives. How about advocating for electronic entertainment that doesn’t provoke seizures?

AAP’s current advocacy priorities on kids and media

The AAP’s Council on Communications and Media policy statement on media use from November 2013 contains a variety of advocacy recommendations, including proposals that pediatricians and the AAP:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming”

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of smoking and without product placements

Proposed changes to above initiatives

Here’s how these points should be expanded to encompass the health risk to unknown numbers of children who experience seizures from flashing visuals:

- Advocate for a federal report within the National Institutes of Health or the Institute of Medicine on the impact of media on children and adolescents, including the neurological impact of flashing screens

- Encourage the entertainment industry to “reassess the effects of their current programming” – including the physiological effects of flashing and high-contrast patterns

- Establish an ongoing funding mechanism for new media research that includes studies on the vulnerability of young people with ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, and mood disorders

- Challenge the entertainment industry to make movies without portrayals of characters smoking and without product placements and to make video games without the flashing and pattern characteristics that can trigger seizures

Question for the AAP Council on Communications and Media

There are many angles and interests that must be considered in making your next policy statement. I have a lot to add to the conversation as far as reducing the risks to young people of screen-triggered seizures, many of which go undetected. Would you accept my assistance? I would be happy to help.

Pediatricians backpedalling on kids’ media use?

Posted: 10/12/2015 Filed under: Health Consequences, Medical Research | Tags: ADHD, American Academy of Pediatrics, autism, computer games, flash, flicker, video games Leave a comment

How much is the American Academy of Pediatrics retreating from its guidelines on media use in children? We’ll find out when the guidelines are in fact changed.

Is the American Academy of Pediatrics changing its recommendations to parents about children’s media use? Not really. Well, yes, in a way. But hard to say. It depends on what you think constitutes a recommendation.

As recently as 2013, the Academy’s official policy on media use discouraged any screen exposure for children under age 2 and recommended less than two hours of screen entertainment after that.

But in a piece in the October 2015 AAP News, after acknowledging that this advice already appears seriously out of step with today’s media environment, the Academy announced it intends to update its guidelines. No date for the update was provided.

Then, in the same article, the Academy proceeded to offer some advice for parents about children and media use, directing parents as follows:

“Play a video game with your kids. Your perspective influences how your children understand their media experience. For infants and toddlers, co-viewing is essential.” [emphasis added]

So, what is going on here? This is kind of murky. Despite some headlines to the contrary, the Academy of Pediatrics does not have a new policy on children’s media use. Instead, concerned about its reputation and trying to stay relevant, the Academy has published a dozen so-called “key messages” regarding media use “to inform and empower families.” Messages, not guidelines.

Key Messages

The key messages are mostly commonsense things like using media alongside your child, setting (unspecified) use limits, creating tech-free zones at home, etc. The messages are decidedly laid-back. Apart from the acknowledgment that “like any environment, media can have positive and negative effects,” the only potential negatives mentioned are sexting, posting self-harm images, and limited participation in other activities.

For the record, I strongly disagree with one of the messages: “The quality of content is more important than the platform or time spent with media.” No, no, no. This assertion runs counter to plenty of research on adverse neurological effects of screens. Platform matters: big screens, flashy images, and extended exposure all increase the risk of seizures and other manifestations of nervous system overload!

Predictably, this month’s key messages are being hailed in some quarters as validation of the safety of electronic media and repudiation of concerns about such safety. For example, in a Forbes piece with the misleading title “The American Academy of Pediatrics Just Changed Their Guidelines on Kids and Screen Time,” Jordan Shapiro writes, “It is about time…the AAP guidelines seemed like they were the result of familiar technophobic paranoia that always accompanies new technologies.” He cites his own words from a previous post:

“At this point, worrying about exposure to screens is like worrying about exposure to agriculture, indoor plumbing, the written word, or automobiles. For better or worse, the transition to screen based digital information technologies has already happened and now resistance is futile.”

It’s easy for Shapiro and others to be dismissive of any health concerns related to media, when the American Academy of Pediatrics’ “key messages” fail to include reminders that there still are health issues to be concerned about. Issuing these bland recommendations may do more harm than good by creating the impression for parents there’s nothing really serious to worry about.

Not So Fast…

The AAP’s key messages around media use resulted from an invitation-only symposium of researchers held in May. An article reporting on the proceedings of that symposium shows that—to their credit—the presenters in fact voiced concerns in a number of areas and called for more investigation of:

- Problematic/addictive media use that is often associated with mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety

- The relationship between media violence and aggressive/violent behavior

- The adverse effects of screen media on sleep

- The need for cultural diversity to be reflected in digital media

In addition, researchers:

- “urged the AAP to not shy away from unpopular recommendations and to formulate policy guided by the best available research”

- Noted that “one size doesn’t fit all with respect to digital interactions…the diversity of youth, families, and communities will influence resilience factors and vulnerabilities”

Unfortunately, few families are likely to know about these concerns, because very few will read the article summarizing the symposium’s presentations and recommendations. They’ll just hear the key messages and relax about it all.

Looking Ahead

One can hope that the next round of formal media use guidelines will thoughtfully incorporate these and other health issues related to digital media use by young people. The account of the proceedings suggests that the guidelines themselves will be more nuanced than the so-called key messages.

In particular I would like to see media guidelines for kids with mood disorders, ADHD, and autism spectrum disorders (ASD), whose brain physiology leaves them more vulnerable to adverse effects. Given government estimates that 13 to 20 percent of children ages 3 – 17 have a diagnosable mental health disorder, these children’s needs should figure prominently in any policy recommendations by the AAP.

“The mission of the American Academy of Pediatrics is to attain optimal physical, mental, and social health and well-being for all infants, children, adolescents and young adults.” — from AAP Facts

Reclaiming a child’s brain from video games

Posted: 08/19/2015 Filed under: Medical Research, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: ADHD, autism, computer games, flash, flicker, neuroscience, seizures, video games Leave a comment Many parents sense that media use affects their children in vague, unseen ways. They’re not imagining it. I have an excellent book to recommend if you’d like to understand more about the way children’s brains–and therefore all aspects of daily function–are stressed by video games. Three years ago I cited a piece by child and adolescent psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley about the effects on the nervous system of interactive screen time. Dr. Dunckley outlined a syndrome of dysregulated mood, attention, executive function, and arousal that develops in response to exposure to video games and other interactive, screen-based applications.

Many parents sense that media use affects their children in vague, unseen ways. They’re not imagining it. I have an excellent book to recommend if you’d like to understand more about the way children’s brains–and therefore all aspects of daily function–are stressed by video games. Three years ago I cited a piece by child and adolescent psychiatrist Victoria Dunckley about the effects on the nervous system of interactive screen time. Dr. Dunckley outlined a syndrome of dysregulated mood, attention, executive function, and arousal that develops in response to exposure to video games and other interactive, screen-based applications.

I’m delighted that last month she published a comprehensively researched, clearly and compassionately written book explaining how interactive screens affect children’s mood, thinking, and arousal, with a lot of practical guidance on how to restore their children. In Reset Your Child’s Brain: A Four-Week Plan to End Meltdowns, Raise Grades, and Boost Social Skills by Reversing the Effects of Electronic Screen-Time, Dr. Dunckley validates parents’ concerns, pulling together research from a range of scientific fields, and in clear language explains screen-time’s effects on the nervous system.

Dr. Dunckley suggests thinking about the stress on the brain from the stimulation of electronics use as not unlike caffeine, amphetamines, or cocaine. She makes a compelling case that the nervous system’s hyperarousal (fight-or-flight response) that kicks in while playing video games sets in motion an array of biological mechanisms that lead to significant functional impairments. She says that seizure activity, along with other tangible symptoms including migraines and tics, is at the extreme end of a continuum of nervous system dysfunction due to the brain’s hyperarousal. Irritability and general nervous system dysfunction are at the other end of the continuum. Other symptoms on that spectrum include mood swings, poor executive functioning, poor impulse control, anxiety, depression, body clock disruption, and immune system suppression.

Dr. Dunckley stresses that the impairments from screen-time are not limited to screen-addicted kids or those who play violent video games, and that playing “in moderation” can still affect a child’s nervous system. Exposure tolerance varies greatly, so some children can resume limited screen use without relapses in behavior and functioning. Those with ADHD or autism spectrum disorders have a greater likelihood of becoming dysregulated by screen exposure. In general, though, the more stimulating the sensory experience, from vivid colors, rapid movements and scene changes, and multi-modal sensory input, and the more frequently the child is exposed to it, the greater the accumulated strain on the nervous system. The greater that strain, the more difficult it becomes for children to control their emotions and behavior.

“Whatever the subject manner, the style or manner in which content is delivered has its own impact. Research indicates that movement, zooms, pans, cuts, and vividness…contribute to repeated fight-or-flight reactions. Screen size affects arousal levels as well, with larger screens producing higher levels of arousal.”

On to the good news: if given respite from overstimulation, the nervous system can restore itself. Dr. Dunckley has treated hundreds of patients whose mood, behavior, and cognitive abilities have been restored after an electronic “fast,” in which electronic screens are set aside for 3 to 4 weeks for an initial evaluation period. In many cases serious limits or total abstinence from screens is necessary to sustain the remarkable improvements in daily functioning that occur. The majority of the book is devoted to practical guidance for parents on how to undertake the daunting task of disentangling a young person from daily screen use.

This book is done extremely well. It begins with a thoughtful synthesis of non-industry-funded research from widely dispersed fields, connecting the dots to show what the body’s response is to environmental stressors. Dr. Dunckley shows considerable respect for parents’ conflicted feelings and their guilt about their own screen habits:

“Let’s face it. Hearing that video games, texting, and the iPad might need to be banned from your child’s life does not fill one with glorious joy. Rather, for many, it creates an immediate urge to find a way either to discredit the information or to work around it…the inconvenience of what I’m proposing can seem overwhelming…some folks feel as though their parenting skills are being judged, or that their efforts or level of exhaustion are underappreciated.”

Dr. Dunckley provides cases from her own practice that show how life-changing the difference can be when a child’s nervous system is given a respite from electronic screens. This is serious business:

“The goal of screen limits is not merely to get rid of bothersome symptoms but to optimize a child’s development over time. All children benefit from screen limits, which have a compounded effect on functioning later in life.”

She is spot on. As some of you know, I’ve been there. Eight years ago it was a bittersweet revelation to see my daughter’s potential reemerge after a long period of impairments and health problems brought on by video game seizures. She lost several years of optimal learning, social development, and health because of frequent seizures we were unaware of during her daily video game use. We didn’t realize just how severely she’d been affected until she swore off gaming and made dramatic gains.

For the record, I don’t hate video games. But I am very disturbed that they can be so damaging to kids’ everyday functioning and potential. Read this book! Share it with your friends, too.

Note: I’ve linked to the book’s Amazon.com page so you can see the very enthusiastic reviews posted there. I am not endorsing Amazon, nor do I have a financial stake in any purchase you may decide to make.

Researchers on a mission ignore seizure studies

Posted: 05/29/2015 Filed under: Health Consequences, Media Coverage, Medical Research | Tags: computer games, epilepsy, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a comment A big reason seizures induced by video games aren’t more widely known is the absence of new research findings about the problem. There continues to be a lot of misinformation out there, and meanwhile we get farther away in time from the studies showing there’s good reason to take the seizure risk very seriously. Without announcements of new results or a concerted education effort by advocacy organizations, it’s tough to keep this issue alive for the public. When today’s researchers of video games miss the opportunity to remind readers of the seizure studies, they perpetuate the public’s disregard for the seizure risk. Here’s why this happens:

A big reason seizures induced by video games aren’t more widely known is the absence of new research findings about the problem. There continues to be a lot of misinformation out there, and meanwhile we get farther away in time from the studies showing there’s good reason to take the seizure risk very seriously. Without announcements of new results or a concerted education effort by advocacy organizations, it’s tough to keep this issue alive for the public. When today’s researchers of video games miss the opportunity to remind readers of the seizure studies, they perpetuate the public’s disregard for the seizure risk. Here’s why this happens:

- The research showing video games can trigger seizures is old news! Many studies on video games and photosensitive epilepsy have already been published, beginning in the early 1980s. The findings and methods have been refined over time, but the results have been fairly consistent. Since there wasn’t much controversy about the studies, the research community has largely moved on from what was already considered a niche subject. More recent studies by these same specialists in photosensitive epilepsy aren’t the type to be appreciated outside the scientific community: research methdologies, specific genes, and the place of reflex seizures in the spectrum of seizure disorders. Not very newsworthy for the general public.

- Most studies today on the effects video game use are about long-term influence on skills, behavior, and attitudes, and on their use in education and health-related applications. These studies are typically done by social scientists, who in general are not including medical issues in their analyses. Studies like this are looking at a different body of previous work–studies done by other social scientists–and the authors may not be familiar with the photosensitive epilepsy research.

- There’s a real backlash these days against studies warning about negative influences of video games. Video games are clearly here to stay; researchers and game developers are eager to demonstrate games’ potential for good. Unfortunately, people who write about video games’ beneficial effects and purposeful applications tend to treat with suspicion (or worse) any earlier studies showing problems attributed to games. Or the seizure issue is omitted altogether from summaries of previous findings.

Seizure research swept under the rug

People who grew up using computers and video games from an early age now comprise a sizeable segment of the research community. Many of them feel there has been a consistently negative bias in studies about video games and they are eager to show another perspective. Here’s an example. Prof. Mark Griffiths in the UK wrote a piece last year entitled, “Video Games Are Good for Your Brain – Here’s Why” that he begins this way:

People who grew up using computers and video games from an early age now comprise a sizeable segment of the research community. Many of them feel there has been a consistently negative bias in studies about video games and they are eager to show another perspective. Here’s an example. Prof. Mark Griffiths in the UK wrote a piece last year entitled, “Video Games Are Good for Your Brain – Here’s Why” that he begins this way:

“Whether playing video games has negative effects is something that has been debated for 30 years, in much the same way that rock and roll, television, and even the novel faced much the same criticisms in their time. Purported negative effects such as addiction, increased aggression, and various health consequences such as obesity and repetitive strain injuries tend to get far more media coverage than the positives.”

Prof. Griffiths had greater difficulty getting his own papers published when they showed positive positive influences of games than when they addressed difficulties such as video game addiction. The article points out positive outcomes using video games for social engagement, therapeutic applications, and education, and then concludes with this irresponsibly inaccurate statement:

“What’s…clear from the scientific literature is that the negative consequences of playing almost always involve people that are excessive video game players. There is little evidence of serious acute adverse effects on health from moderate play.” [However, there is extensive evidence of seizures–a pretty serious acute adverse effect–that can occur even with very brief exposure. — JS]

Social scientists pick and choose

Earlier this year a piece titled “Video games can be good for you, new research says” (no link because it’s behind a pay wall) appeared in the Chicago Tribune. The reporter opens the piece by putting video game research into historical context.

“Researchers have done thousands of studies on gaming since the 1980s, often with unmistakably negative results. Some associated video games with an increased risk of epileptic seizures, while others cautioned that the games could provoke dangerously elevated heart rates. Many studies also linked violent games to aggression and anti-social behavior.”

Then the article turns to a psychology professor whose new study forms the basis of the article. Prof. Christopher Ferguson has done dozens of studies on effects of video game use. Prof. Ferguson, who’s found that violent video games do not contribute to societal aggression, reasons that early research into any new technology is often flawed. Studies that aim to find negative effects get funded and promoted, while those with more benign findings are unpublished and forgotten, he explains.

Then the article turns to a psychology professor whose new study forms the basis of the article. Prof. Christopher Ferguson has done dozens of studies on effects of video game use. Prof. Ferguson, who’s found that violent video games do not contribute to societal aggression, reasons that early research into any new technology is often flawed. Studies that aim to find negative effects get funded and promoted, while those with more benign findings are unpublished and forgotten, he explains.

“When a new generation of scholars more familiar with the technology comes along, different results often appear — and that’s what is happening with gaming. We’re just not seeing the kind of data emerge that would support the techno-panic that was common in earlier years.”

There is no further mention in the article of studies about the video game seizure problem–as if all the video game seizure research was part of the so-called “techno-panic.”

I contacted the Tribune reporter to point out that the seizure problem is for real and hasn’t gone away. He said he was aware of this fact and was interested in writing about it sometime. However, without a piece of news tied to it, such as results from a new study, other stories are obviously much more compelling for a newspaper to cover.

P.S. I’m on a mission, too

I’ve chosen to focus on the seizure risk from exposure to video games, and on the after-effects these seizures–even small ones–can have. If you’ve read other posts of mine, you’re aware I believe there is still some research on video game seizures that needs to be done and it’s on issues that could produce newsworthy results:

- the higher risk of visually induced seizures in specific populations, such as young people with autism. One small, unpublished study found 25 percent of young people over age 15 with autism spectrum disorders are photosensitive, but more study is needed.

- the real prevalence of photosensitive seizures, which researchers admit are probably underdiagnosed because they aren’t noticed or reported.

So, what’s new on the seizure thing?

Posted: 02/25/2015 Filed under: Media Coverage, Medical Research | Tags: computer games, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games Leave a commentThere are many reasons for low awareness of the seizures induced by video games, but today I want to focus on a big one: the lack of current research.

Without new research or a concerted outreach effort by advocacy organizations, it’s tough to keep the issue alive in the media. New research means new findings to announce. The press isn’t likely to cover a subject that’s producing no news.

It’s not as if conclusive studies don’t exist on seizures triggered by video games. Many clinical studies on video games as a cause of photosensitive seizures have been published, beginning in the early 1980s. The findings and methods have been refined over time, but the results have been fairly consistent and haven’t stirred up controversy. In fact, photosensitive epilepsy has always been considered a niche disorder and an out-of-the-way area of research. What’s left to prove?

Today’s studies involving video games are all about how games influence behavior and attitudes. Social scientists are investigating questions such as how much video games affect cognitive performance, memory, physical response time, behavior, and attitudes about violence. The results of ongoing studies like this—unlike the old news about seizures triggered by video games–frequently appear in the news media, keep the issues alive, and are topics of public debate.

The last time significant research findings were published and the advocacy community acted upon this public health problem was in 2005, when consensus papers on photosensitive seizures were published and the Epilepsy Foundation acted by issuing new guidelines for families on preventing them. Very little has occurred or has been published since then to keep the issue before the American public. (One exception: in 2008 the Epilepsy Foundation publicly responded to an Internet attack that placed seizure-inducing images on its website.)

Here’s an example of how things work in the news business.

Last month a pretty balanced piece titled “Video games can be good for you, studies say” appeared in the Chicago Tribune. The reporter, John Keilman, begins the piece by putting video game research into historical context.

Researchers have done thousands of studies on gaming since the 1980s, often with unmistakably negative results. Some associated video games with an increased risk of epileptic seizures, while others cautioned that the games could provoke dangerously elevated heart rates. Many studies also linked violent games to aggression and anti-social behavior.

Then the article turns to Christopher Ferguson, a psychology professor at Florida’s Stetson University who’s found positive contributions of video games:

Ferguson has done dozens of studies on the subject and has consistently found that violent video games do not contribute to societal aggression. One recent project actually concluded that some children who play violent games are less likely than others to act like bullies. [That’s pretty newsworthy!–JS] Ferguson said early research into any new technology is often flawed. Studies that aim to find negative effects get funded and promoted, while those with more benign findings are unpublished and forgotten, he said. When a new generation of scholars more familiar with the technology comes along, different results often appear — and that’s what is happening with gaming, he said. “We’re just not seeing the kind of data emerge that would support the techno-panic that was common in earlier years,” he said.

Although Keilman balanced Ferguson’s remarks with quotes from another researcher, who’s quite skeptical about recent positive findings, there is no further mention in the article of studies about the seizure problem. Readers can easily assume that—as with early studies linking violent games to violent behavior—all the research showing video games can trigger seizures stems from the “negative attitude by technophobes” in the early days of gaming. If one follows Prof. Ferguson’s line of thinking, one could expect that newer studies—if there are any–on seizures and games can be expected to reverse the earlier studies.

I contacted Keilman to point out that the seizure problem hasn’t gone away. He responded that he was aware of this and was interested in writing about it sometime. He also mentioned continuing research on the seizure issue. I think he’d be interested in writing about the subject if there was some new study that’s newsworthy, but there simply isn’t.

In the absence of new research, or a Pokémon-type episode, it’s hard for journalists to write about a topic that just isn’t news.

Study challenges reliability of EEG test for photosensitivity

Posted: 07/19/2014 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Research | Tags: EEG, photic stimulation, photoparoxysmal response, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, video games Leave a commentIf the results of a recent study at SUNY at Buffalo are any indication, there are an awful lot of people vulnerable to visually induced seizures who are being told they aren’t at risk. The study showed that testing for photosensitivity using EEG with photic stimulation provides unreliable information. In the wake of these findings, ruling out photosensitive epilepsy–and ignoring the seizure risk from video games–simply on the basis of intermittent photic stimulation results would seem very unwise.

This study–not yet published–by the Buffalo research team found that the test is poorly correlated with vulnerability to visually induced seizures in everyday life. Just 6.2 percent of patients with a history of visually provoked seizures tested positive for photosensitivity.

The standard test for photosensitivity is intermittent photic stimulation—a strobe light flashing at specified frequencies—while hooked up to EEG. Abnormal waves provoked by the photic stimulation are known as the photoparoxysmal response (PPR). (To avoid triggering a seizure during the procedure, the flashing is halted as soon as any of these abnormal waves appear.)

Researchers have known for a long time that many people who test positive never actually experience photic seizures. The Buffalo study confirms this: of 86 patients whose EEG yielded a PPR, just 13 (15.11 percent) reported having experienced visually triggered seizures. What’s new here is the finding that many people who test negative do actually experience these seizures.

The investigators, led by Novreen Shahdad, MD, initiated their study after a patient with a clear history of seizures provoked by electronic screens did not test positive for photosensitivity. “With the increasing popularity of video games and parental concern of their predisposition for seizures,” the authors wrote, “there is a need to identify individuals at risk for PIS [photic induced seizures].”

Find the above summary on page 14 of the 2012 SUNY at Buffalo School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Residents Research Day program schedule

Shahdad and her colleagues examined a Buffalo EEG database and found 129 patients between 1999 and 2013 who reported seizures triggered by TV, computer use, and video games. Of those patients, a total of 8 tested positive for photosensitivity. Thirty of the 129 patients had reported a history of video game seizures. Of those 30, only one showed a photosensitive response on EEG!

Photosensitivity is defined by researchers as the appearance on EEG, in response to photic stimulation, of certain spike and wave patterns characteristic of epilepspy. Note that the criterion for photosensitivity is not the occurrence of visually induced seizures in everyday life—it refers only to the strobe test.

The study concluded:

“In contrast to the general impression, our study did not find a significant association of a positive response to photic stimulation in patients with photic induced seizures (PIS). This association was seen only in 6.2% of patients with PIS. In addition, PPR on EEG was not associated with statistically significant increase of PIS. Hence we conclude that PPR cannot be used as an isolated predictor for PIS.”

I’ve previously raised questions about diagnosing vulnerability to visually induced seizures soleley on the basis of EEG response to photic stimulation. More study is certainly warranted.

Disenfranchisement of reflex seizures ending?

Posted: 04/16/2014 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Medical Research, Photosensitive Seizure Prevention, Political Action & Advocacy | Tags: computer games, epilepsy, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures, video games Leave a comment

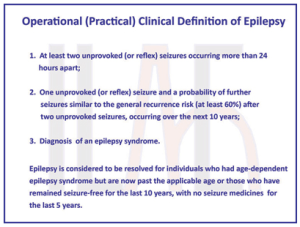

The new definition of epilepsy makes it clear that reflex seizures “count” as evidence of epilepsy. In previous definitions, this was not explicity stated.

A new definition of epilepsy published this week affirms that photosensitive and other reflex seizures qualify as “real” epilepsy. This clarification may eventually help increase awareness of seizures from video games and other electronic media.

Although reflex seizures have long been included in official classification schemes of epileptic seizures, they don’t fit cleanly into established categories of seizure types and epilepsy syndromes. In neurology training they are typically mentioned only briefly. And typically they are taken too lightly by doctors using the prevailing diagnostic criteria for epilepsy: at least two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart.

Because reflex seizures, by definition, are provoked by specific triggers, there’s confusion and most doctors have been reluctant to diagnose epilepsy in people whose epileptic seizures require an environmental provocation. The authors of the new definition paper acknowledge this:

“Under limits of the current definition, [a] patient might have photosensitive epilepsy, yet not be considered to have epilepsy because the seizures are provoked by lights…People with reflex epilepsies previously have been disenfranchised by the requirement that seizures be unprovoked. The inclusion of reflex epilepsy syndromes in a practical clinical definition of epilepsy now brings these individuals into the epilepsy community.”

Diagnostic criteria under the new definition now include at least two unprovoked or reflex seizures at least 24 hours apart. The new definition also allows an epilepsy diagnosis after a single seizure–either unprovoked or reflex–if there is a high probability of recurrence.

I’ve written previously about the inconsistency inherent in using the criterion of “unprovoked” to diagnose epilepsy in people whose seizures happen only in response to sensory triggers such as flashing light. This thinking (along with the assumption that photosensitive epilepsy is very rare) has led to marginalization of reflex seizures in the research community and among clinicians as well. Marginalization means doctors have been underdiagnosing reflex epilepsy, researchers seeking funding pursue other topics to study, and the public and public policy makers are largely unaware of the public health issue of photosensitive seizures.

The practical clinical definition was developed by a 19-member multinational task force of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE), incorporating input from hundreds of other clinicians, researchers, patients, and other interested parties. I’m more than pleased that the ILAE is choosing to make it clear that reflex epilepsy deserves the same respect as other forms of the disease (the new definition paper characterizes epilepsy as a disease rather than a disorder). It’s fortunate that the chair of the ILAE task force that produced the new definition is Robert Fisher, MD, PhD of Stanford, lead author of the 2005 consensus paper describing seizures from visual stimulation as “a serious public health problem.” No doubt Dr. Fisher’s appreciation of the magnitude of the problem was instrumental in ensuring that the task force addressed it.

Not all epileptologists agree with all aspects of the new epilepsy definition–and Epilepsia has given them a voice as well, publishing half a dozen commentaries, all of which are available free online. I contributed a piece as well, providing a patient/family perspective.

Of course, it remains to be seen how long it will take for neurologists to shift their attitudes and diagnostic practices regarding reflex epilepsy. Perhaps the inclusion of reflex seizures in the epilepsy definition will help dispell the idea that reflex seizures are rare.

“Problematic” gaming higher in autism, ADHD

Posted: 07/29/2013 Filed under: Medical Research, Seizure Risk | Tags: ADHD, American Academy of Pediatrics, autism, computer games, EEG, photosensitive epilepsy, seizures, video games 1 Comment A study released today in the journal Pediatrics confirms what a lot of parents have already figured out: kids with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and kids with ADHD spend much more time playing video games than typically developing peers and “may be at particularly high risk for significant problems related to video game play, including excessive and problematic video game use.” Only boys participated in the study merely because both disorders are diagnosed more frequently in boys–there is no reason to expect the results would be any different if girls were included.

A study released today in the journal Pediatrics confirms what a lot of parents have already figured out: kids with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and kids with ADHD spend much more time playing video games than typically developing peers and “may be at particularly high risk for significant problems related to video game play, including excessive and problematic video game use.” Only boys participated in the study merely because both disorders are diagnosed more frequently in boys–there is no reason to expect the results would be any different if girls were included.

The study notes that in the general population, long-term. excessive video game use can have a variety of detrimental effects. “Although longitudinal research [collecting data on a group of subjects over an extended time] is needed to examine the outcomes of problematic video game use in these special populations…the current findings indicate a need for heightened awareness and assessment of problematic video game use in clinical care settings for children with ASD and ADHD.” Of course, many kids start playing video games before they are diagnosed with ASD or ADHD, so maybe the heightened awareness and assessment should extend to all kids?

Well, this is a first step, to compare, as this study did, behavioral characteristics and game usage of neurotypical kids against kids with ASD and ADHD. The problem with these studies is that all they can point to is associations between behaviors and game use in the three cohorts. No causality. There’s an association between attention problems and problematic video game use, which means the attention problems could already exist or could be the result of game use (or both, probably). The study calls for longitudinal studies (following the participants over a long period of time) “to examine the long-term effects of screen-based media use in children with ASD.”

Without waiting for the results of a longitudinal study, researchers could find out pretty quickly how the brain responds to video games in kids with ASD and ADHD and in neurotypical peers. Hook up all three groups to an EEG while they play, note the differences in the way their brains react. Track brain activity when they aren’t playing, and compare it to their activity in front of a game. This provides the opportunity to show causality. Despite the drawbacks of EEG, it’s the most practical tool for this type of study.

I’m willing to bet that the rate of seizures (especially the kind you can’t see) detected during playing is higher in the ASD and ADHD kids. The seizures and seizure-like abnormalities in brain waves have an immediate effect on cognitive function (including attention/focus)and behavior. Inability to focus is a very common post-seizure symptom, and it can last for a day or two after a seizure. A child who plays video games often and who has this sort of neurological response to video games may therefore exhibit inability to pay attention and other behavioral difficulties all the time.

I’m still eager to have researchers take up the pilot study I proposed a few years ago that looks at the EEGs of ASD kids and neurotypical kids, both at rest and while playing video games. In the meantime, whether or not the studies are telling us something totally new, if they encourage parents to think more carefully about their children’s gaming habits and question possible links to behavior issues, that’s a good thing.

Bread and video games

Posted: 11/08/2012 Filed under: Diagnostic Challenges, Health Consequences, Medical Research | Tags: celiac, computer games, EEG, flash, gluten intolerance, photic stimulation, photosensitive epilepsy, photosensitivity, seizures 1 CommentWhat do a loaf of bread and an action video game have in common? Both are man-made and widely consumed, yet hugely underrecognized as potentially serious health hazards. There are a lot more parallels.

Sensitivity to gluten, the primary protein in wheat, and to the bright flash and rapidly moving patterns game of screens, are both considerably more pervasive than the medical community and the general public had realized. Awareness of gluten sensitivity has grown tremendously in the past decade, though, because a portion of the medical community broadened its understanding of a disorder once defined by very rigid diagnostic criteria.

Consider this comparison:

Progress on the gluten front

For decades the only type of gluten sensitivity recognized by doctors was celiac disease, a severe condition that often, but not always, manifests with gastrointestinal problems. The only diagnostic testing required an intestinal biopsy that–turns out–is easily falsely negative. After a negative biopsy, would be told that celiac disease had been ruled out, and that therefore it was OK to eat wheat and other grains containing gluten. In actuality many of these patients either had celiac–but a misleading biopsy that didn’t collect tissue samples from the affected area of the intestine–or they had a different form of gluten sensitivity that causes damage only to other body organs, rather than the intestine.

Because doctors were taught in medical school that celiac disease is very rare, occurring in only one in several thousand individuals, there seemed to be little reason to consider the diagnosis in patients, order a biopsy, or question a negative biopsy result. Some researchers suggest that ten percent or more of the American public has a sensitivity to gluten, in most cases with no obvious symptoms or symptoms that don’t suggest a food sensitivity. Even without obvious symptoms gluten intolerance can be a very serious disorder that affects daily functioning and quality of life.

Growing numbers of consumers without an official diagnosis of gluten sensitivity are being more proactive by experimenting on their own with a gluten-free diet as a healthier way to eat. Many notice a range of improvements in their well-being from this change. A rapidly expanding market of prepared gluten-free foods makes a gluten-free lifestyle less burdensome. An increasing number of restaurants offer gluten-free menus, and new gluten-free foods are a booming market for food retailers. Celiac and gluten-free support groups provide practical and moral support. In addition to peer-reviewed research, there are now a lot of books for consumers and online resources. Probably most consumers are learning about gluten sensitivity from these sources rather than their clinicians, and some are helping educate their doctors about it.

The photosensitive epilepsy front

Because doctors were taught in medical school that photosensitive epilepsy is very rare, occurring in only one in several thousand individuals, there has seemed to be little reason to consider the diagnosis in patients, order an EEG with photic stimulation, or question a negative or inconclusive EEG. There is no practical, reliable way to know how prevalent photosensitive epilepsy is in the general population. Even without obvious symptoms of a seizure, people who experience subtle seizures can experience impairments that affect daily functioning and quality of life.

Without an official diagnosis of photosensitivity, consumers can experiment with a screen-reduced or screen-free lifestyle–should they have an inkling that subtle seizure activity caused by screen exposure is affecting their health. However, at this time there are few products or supports to help them cut back on recreational screen time. A limited number of mental health providers offer therapy for Internet or video game addiction. Most focus on treating the addiction itself rather than on overcoming the physical and mental health consequences of exposure to potentially seizure-causing screens. Consumers are still essentially on their own to figure out the connection between video games and seizure activity, and there is little for them to read on the subject. Little research is being carried out in the US on photosensitivity and today’s electronic entertainment.

Perhaps there is reason to be encouraged by the progress in educating the public and clinicians about gluten-related health problems. In the face of similar obstacles to wider awareness and prevention, it should be possible for seizures induced by visually overstimulating electronic media to become better known, understood, and prevented. In the interim, a great deal of work lies ahead to empower consumers with the information they deserve about screen-induced seizures. Please help spread the word.